Everything You Need To Know About Getting A Hysterectomy

Hundreds of thousands of people with female reproductive organs undergo hysterectomies every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). By the age of 60, there is a 33% percent chance that a woman will have had the operation (via CDC). Dr. Lauren Streicher, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, adds that over 85% of those who had the operation report being glad that they went through with having a hysterectomy. Despite this, the surgical procedure is surrounded with myths and misconceptions, explains Dr. Streicher.

If your physician mentions the possibility of this operation — or if a friend or family member undergoes it and is enthusiastically telling you about all the benefits — there are probably a lot of questions that will crop up. Who should consider getting a hysterectomy? What is are the risks of the surgery, and what is the recovery like? Do I have any alternatives to explore before landing on the operating table? Here is everything that experts say you should know before committing to this major surgery that changes women's anatomy.

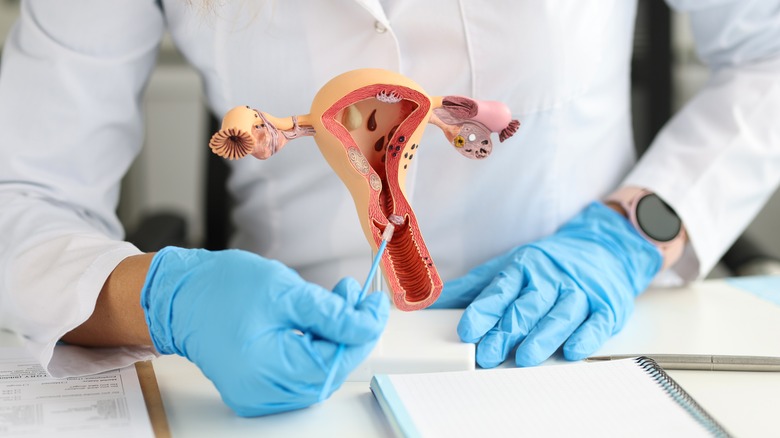

A hysterectomy is removal of the uterus

So we are led to one of the first important questions to answer before choosing a hysterectomy: What, exactly, is it? Per WebMD, this operation removes all or part of the uterus, the organ within the female reproductive system that holds a developing fetus during pregnancy. The uterus is hollow and pear-shaped, located in the lower abdomen (via Johns Hopkins Medicine). When not pregnant, the uterus is only about 3 inches long from top to bottom, 2 inches wide, and 1 inch thick, says the Cleveland Clinic. The organ weighs just 1 ounce. The uterus is connected to the vagina via the cervix, and is situated in between the bladder and the rectum.

The uterus is also connected to the ovaries by way of the fallopian tubes. Ovaries produce eggs, and the eggs travel through the fallopian tubes to the uterus. This organ is also responsible for your monthly menstrual cycle; unless a fertilized egg implants into the uterine lining, the uterus sheds its inner tissue lining, called the endometrium, during the monthly cycle, according to Cleveland Clinic.

Potential reasons for a hysterectomy

You are more than likely experiencing one of the situations described here if hysterectomies have become an option for you. As the National Health Service explains, hysterectomies can be done at a physician's recommendation to treat a condition like uterine prolapse or invasive cancer in the female reproductive organs, including the uterus, vagina, cervix, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. A hysterectomy may also happen in the case of an emergency such as life-threatening bleeding or infections, or complications during childbirth. According to MedicineNet, other conditions that doctors might recommend a hysterectomy to treat include uterine fibroids and growths and severely excessive menstrual bleeding.

Hysterectomies can also be elective (requested by the patient) as a means of surgical sterilization, but many doctors may recommend other methods to prevent pregnancy before suggesting this procedure. In this case, there are a number of permanent birth control methods alternative to hysterectomy, including hysteroscopic sterilization and tubal ligation.

About your operation and hospital stay

According to the Mayo Clinic, some things may occur before the operation, including a Pap smear, biopsy, or ultrasound, to gather more information about the reason for the hysterectomy, especially if cancer affecting the reproductive organs is suspected. Your surgeon may instruct you to shower with a special infection-preventing soap, and may order a douche or an enema, the day and morning before surgery. Right before your hysterectomy takes place, you'll be administered an antibiotic by IV to minimize risk of infection. The operation is done by a gynecologist, takes a couple of hours, and occurs under general anesthesia — meaning you'll be unconscious.

After your operation, you will receive medications to alleviate pain and discomfort, says Mount Sinai, and there will likely be a catheter in use for a while after the surgery ends. Your hospital staff may encourage you to stand up and move about once you're in the recovery room, to prevent the formation of blood clots. Hospital stays typically range from discharge the next day to three days later depending on the type of hysterectomy. In some cases where other medical issues are involved, like when a hysterectomy is due to cancer, the stay may be longer.

Hysterectomy can be abdominal or vaginal

The specifics of the operation will depend on the type of hysterectomy chosen for you. Some types of hysterectomies are less invasive than others, depending on the type and location of the incision. No matter which route taken, at least one incision is required to access the uterus, explains Mount Sinai. This incision may be made into the lower abdominal area or through the vagina. In some cases, hysterectomies can be laparoscopic or robotic, where thin instruments are used through smaller incisions (via Mayo Clinic).

An abdominal hysterectomy might be chosen for a few reasons, including: The gynecologist wants to check other organs in the pelvic area for signs of cancer, or you have a larger-than-normal uterus. This medical history will also determine the type of abdominal incision. As the Mayo Clinic explains, abdominal procedures are made with either vertical incisions (extending from underneath the navel to above the pubic bone) or horizontal incisions across the bikini line, similar to a Cesarean incision. Vertical incisions are typically chosen for hysterectomies due to fibroids, cancer, or endometriosis.

Hysterectomies can be partial, total, or radical

By definition, a hysterectomy only impacts your uterus, but depending on your diagnosis or reason for getting a hysterectomy, your doctor may also choose to remove other organs along with it. According to Nava Health, a partial hysterectomy, also called a supracervical hysterectomy, changes the internal pelvic structure the least by only removing part of the uterus but leaving the cervix intact. On the other hand, a total hysterectomy will remove the entire uterus and the cervix. With this type of surgery, the doctor must suture shut the internal opening of the vagina where it formerly connected to the cervix. This is called a vaginal cuff.

The last type of operation is a radical hysterectomy, in which case a part of the vagina is removed in addition to the uterus and cervix. The fallopian tubes, ovaries, and nearby lymph nodes may also be removed during the surgery. Vaginal reconstructive cosmetic surgery may be recommended after this procedure. According to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, radical hysterectomies are typically chosen for cancer patients, particularly in the case of cervical cancer. And researchers discovered an interesting trend: Cervical cancer patients who underwent open radical hysterectomies — hysterectomies done through an abdominal incision rather than a minimally invasive (robotic, laparoscopic) — were four times more likely to experience remission and had higher survival rates overall.

Hysterectomy versus oophorectomy

When researching the different types of hysterectomy, you may see frequent mention of the additional removal of surrounding tissues and organs, particularly the fallopian tubes and ovaries. The ovaries are the small, almond-shaped organs in either side of the uterus that produce eggs and the important female hormones estrogen and progesterone. The removal of ovaries is called an oophorectomy, explains the Mayo Clinic. This procedure might target only one ovary — called a unilateral oophorectomy — or it might target both in a bilateral oophorectomy. Hysterectomies mostly impact your physical anatomy, while removing the ovaries will also change your hormone levels and rate of menopause.

Oophorectomies might be done to treat abscesses in the ovaries, ovarian cancer, endometriosis, benign tumors or cysts, torsion (twisting) of an ovary, or as a preemptive treatment for patients at risk of cancer. Hysterectomies and oophorectomies are sometimes done simultaneously, but only when medically necessary, says MyHealth Alberta. Doctors may recommend ovary removal in addition to a hysterectomy if you have the BRCA (breast cancer) gene, a family history of ovarian cancer before 50, severe premenstrual syndrome, or pelvic pain involving ovaries. Oophorectomies come with their own set of risks, including increased chance of osteoporosis and heart disease, and are not needed to obtain a hysterectomy.

Menstruation isn't possible after hysterectomy, but a rare ectopic pregnancy can occur

Perhaps some of the best news women get when they choose to undergo a hysterectomy that the days of cramping, aching, and bleeding are over. When you no longer have a uterus to shed its inner lining, a period becomes impossible (per the New York State Department of Public Health). Pregnancy is not impossible, however, in the event that a bilateral oophorectomy did not occur along with the hysterectomy. For instance, 2015 review published in Case Reports in Women's Health outlines the instance of a woman who came to the emergency room with vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, and vomiting. Despite having had a partial hysterectomy two years prior, the woman tested positive on a pregnancy test. The hospital discovered that a fertilized egg had implanted in her fallopian tube, causing it to rupture.

Referred to as cervical stump pregnancies (since the cervix and part of the uterus remains intact after a partial hysterectomy), these ectopic pregnancies are extremely rare, but can be fatal. Indeed, one report from the Journal of Medical Case Reports states that any woman of reproductive age that comes to the ER with pain in the abdomen and/or pelvis, regardless of hysterectomy history, should be checked for pregnancy if she has at least one ovary and "means for sperm to meet egg." Pregnancies occurring in the fallopian tube or anywhere outside of a whole uterus are not viable and should be treated as an emergency, per The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Hysterectomy risks include bladder or bowel problems, among others

Most medical procedures come with risks and potential complications, and hysterectomies are no exception. The National Health Service (NHS) explains that, like with any surgery, there is a slight chance for adverse side effects to the general anesthesia, including nerve damage and allergic reaction. Rarely, patients will experience bleeding or hemorrhage after the surgery, and there's a 1% chance that your ureter (which passes urine from the kidneys to bladder) will be damaged and subsequently repaired during surgery.

All surgeries also run the risk of infection; with hysterectomies, this could include a wound infection or a UTI. The remaining organs in the reproductive system may also suffer side effects from the operation. Total or radical hysterectomies may be prone to vaginal prolapse, in which the vagina moves out of position, potentially leading to pain, bulging, and bladder and bowel issues (via Cleveland Clinic). Additionally, any hysterectomy without complete oophorectomy runs the chance of ovary failure, since those ancillary organs received part of their blood supply from the now-removed uterus (via NHS). While still rare, it's important to watch for signs that the removal of the uterus has caused damage to critical surrounding organs. Signs of bowel or bladder damage could include incontinence, frequent urination, or infection.

Pelvic floor care after surgery is crucial

Hysterectomies cause a lot of change in your pelvic area. As explained by the Mayo Clinic, during a hysterectomy the uterus is removed, and therefore detached from its surrounding organs — ovaries, fallopian tubes, and cervix or vagina depending on hysterectomy type — as well as the network of blood vessels and tissue that holds the uterus in place. Because of this significant change and the space left behind by the uterus, pelvic floor therapy is critical to helping the body adjust and recover. The organs that remain in the lower abdomen will move around slightly to fill in the void created by the uterus removal; this shift can cause incontinence among other issues, per Nava Center. You may notice changes in your bathroom habits as the bowels adjust: Urges to defecate, cramping and constipation, irregular bowel movements, and bowel incontinence are possible. According to the Nava Center, bowel problems should be resolved a few weeks after surgery.

To aid in this adjustment and battle back the risk of pelvic organ prolapse after a hysterectomy, give your pelvic floor some extra attention. According to Pericoach, some helpful strategies include Kegel exercises, actively preventing constipation, addressing chronic coughs that stress the pelvis, and choosing a healthy diet. Preexisting pelvic floor problems before a hysterectomy, as well as multiple child deliveries, are the greatest risk factors leading to prolapse issues post-op, Pericoach says. Ask your gynecologist for suggestions on pelvic floor protection before your surgery so a therapy plan is in place.

Hysterectomies alone don't cause premature menopause or other hormone disruption

One of the most common hysterectomy myths is that you are doomed to enter menopause practically at the moment you're off the operating table (via Dr. Lauren Streicher). But this is not true per se, which might be confusing: After all, a hysterectomy removes the uterus, you can't have a period without a uterus (via American Migraine Foundation), and menopause is often defined as the time when a woman permanently stops having her period.

However, as Johns Hopkins Medicine notes, menopause can be more precisely defined as the time when a woman's hormone levels begin to shift — namely, her levels of progesterone and estrogen decline. Indeed, it's the decline in these hormones that is responsible for most menopause symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, and mood changes. And as Endocrine Society points out, these hormones aren't produced by the uterus, but by the ovaries. Given this, unless your hysterectomy is accompanied by an oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries), your body will continue to produce the hormones responsible for sexuality and libido even after the uterus has been removed. Since oophorectomies only occur in medically necessary cases, your chances of keeping your ovaries after your hysterectomy — and warding off symptoms of menopause — are good. Even losing the cervix and part of the vagina won't affect your endocrine system, says Dr. John Macey.

If you are under 50 years of age and experience the symptoms of menopause after a hysterectomy — including hot flashes, night sweats, difficulty with vaginal lubrication, urinary incontinence, pain during sex, or mood changes — consult your gynecologist.

Hysterectomies require up to eight weeks to heal

Your body needs plenty of time to rest and heal after this surgery. The hardest moments immediately after surgery will be spent in the hospital, but you should anticipate complete recovery taking up to eight weeks, per the NHS, and your doctor will likely have you return between weeks four and six of recovery to make sure everything is going smoothly.

The NHS adds that recovery tends to take less time in the cases of vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomies, and Dr. Lauren Streicher states that advancements in hysterectomy procedures even make same-day discharge possible in laparoscopic and robotic operations for women with minimal risk of complication. While you may feel your energy levels and mobility returning to normal sooner than eight weeks after surgery — Dr. Streicher explains that some patients even feel "like nothing happened" just a couple weeks after surgery — it's important to go slow, listen to your body, and take as much rest time as needed to allow all the wounded tissues to heal. Women who don't work labor-intensive jobs may feel ready to return to work around two or three weeks after surgery, per Professionals for Women's Health.

Impacts of smoking on healing and recovery

Smoking is a lifestyle choice that significantly increases risk for complications or death after any surgery, according to WebMD. Smokers experience these elevated risks after a hysterectomy: a 40% higher risk of death after surgery than non-smokers, a 57% higher chance of cardiac arrest, an 80% higher chance of having a heart attack, and a 73% higher chance of having a stroke. The risk of pneumonia also doubles, potential for infection spikes, and the likelihood of complications requiring ventilation increases. WebMD states that the reason for these heightened risks is the chronic inflammation caused by smoking.

Patients that smoke and have a hysterectomy may also find their surgical wound taking longer to heal, according to the WHO. This is because of the patient's decreased oxygen levels and diminished immune function. However, WHO studies suggest that quitting smoking at least four weeks before a hysterectomy can lower the risks of complications with the surgery, anesthesia, or healing. However, a study in the journal Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica found that smokers have slightly lower risk of all these complications if they undergo vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Intimate life should be paused during recovery, but may improve after hysterectomy

It's best to put a pause on your intimate life while your body is healing from your hysterectomy. The NHS recommends waiting four to six weeks after your surgery to engage in sexual activity to give your incision time to heal and to allow your body to pass vaginal discharge related to the procedure. An initial drop in libido can be normal, but this should resolve.

There is actually some evidence that your post-hysterectomy sex life, rather than being diminished, can improve. The NHS notes that pain during sex is reduced in most patients after the surgery, while libido and the intensity of orgasm may increase. Indeed, according to a 1999 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the number of women experiencing pain during intercourse fell by 15% after a hysterectomy; and while around 10% of the study participants reported low libido prior to the surgery, only about 6% reported it afterward.

That said, if your hysterectomy is accompanied by an oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries), you will face some hormonal changes that can cause lower libido, vaginal dryness, and discomfort during sex. But as Blueheart points out, this doesn't signal the end of a healthy sex life. Attempting new positions, using ample lubrication, and taking hormone replacement medication are some strategies that can help you maintain sexual intimacy.