Everything You Need To Know About Shellfish Allergies

Shellfish are aquatic animals with a shell-like exterior, and include shrimp, crab, lobster, clams, and oysters (via the Cleveland Clinic). An allergy to shellfish can cause anaphylaxis, a severe and potentially life-threatening reaction. Thus, people with a confirmed diagnosis of shellfish allergy are advised to keep an EpiPen (injectable epinephrine) with them at all times.

Shellfish allergy is among the eight most common food allergies in the United States, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. While very common in children, shellfish allergy is much more common in adults, having a fivefold higher prevalence rate. As noted by the NIH, true shellfish allergy is a type of food allergy mediated by a person's immune system, specifically the antibody IgE (immunoglobulin E). Other reactions to shellfish are not considered true allergies because they are not immune-mediated; rather, they are triggered by pathogens such as parasites, bacteria, and viruses.

An immune-mediated food allergy occurs when the immune system mistakenly recognizes food proteins (e.g., shellfish protein) as pathogens and subsequently produces IgE antibodies (per a 2018 study published in Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology). The IgE antibodies then bind to receptors on certain types of immune cells known as mast cells and basophils. The immune system is now sensitized to the shellfish proteins such that subsequent consumption of shellfish triggers the release of histamine and other inflammatory chemicals that lead to the development of mild or severe clinical symptoms.

Clsssification of shellfish

Per Food Allergy Research & Education, shellfish are subdivided into crustaceans (e.g., shrimp, crabs, lobsters) and mollusks (e.g., oysters, clams, mussels). Crustacean shellfish allergy is the most common type, among which shrimp allergy is the most prevalent.

A food allergen is the specific food component, usually a protein, that triggers immune cells to react (via U.S. food allergy guidelines published in Nutrition Research). Cross reactivity among different foods occurs when the foods share a common or structurally similar allergen, potentially causing similar adverse reactions. According to a 2016 review in Allergo Journal International, there is a large degree of clinical cross-reactivity among and between crustaceans and mollusks. This is due to tropomyosin, the major allergen shared by all species of shellfish. Cross-reactions are especially frequent among the crustacean shellfish. For example, per a 2011 study in Clinical and Translational Allergy, people who have a shrimp allergy typically react to other shellfish in the crustacean group. Moreover, a person with a crustacean shellfish allergy also frequently reacts to members of the mollusk family.

The major allergen in fish (e.g., salmon, tuna) is parvalbumin, which does not cross-react with the tropomyosin allergen common to shellfish, notes a review published in a 2017 edition of Allergy. Thus, a person with a shellfish allergy should not be concerned about eating fish and vice versa. Moreover, neither tropomyosin nor parvalbumin contains iodine (via a 2014 practice update in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology). Therefore, though seafood contains iodine, seafood allergy in not related to iodine sensitivity.

Prevalence of shellfish allergy

Worldwide, shellfish allergy is one of the most common food allergies, affecting up to 10.3% of the general public and increasing, according to a 2020 study published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Unlike children who outgrow egg and dairy allergies, people with shellfish allergy usually have it for life.

Allergic reactions to shellfish occur for the first time in adulthood in 60% of cases, per Food Allergy Research and Education. In the United States, a 2019 survey of more than 40,000 adult Americans found that shellfish had the highest prevalence among the most common food allergies, affecting roughly 7.2 million U.S. adults (via JAMA Network Open). The rate of allergy to shellfish more than doubled that of tree nut and more than tripled that of wheat, egg, and soy.

As a cause of life-threatening anaphylaxis in the U.S., shellfish ranks third only behind peanuts and tree nuts. Among adults exclusively, shellfish allergy is the leading trigger of food-related anaphylactic reactions (per the 2020 study). Nevertheless, more than 40% of adults with shellfish allergy experience only mild-to-moderate reactions rather than severe reactions (via a 2019 study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology).

Causes of shellfish allergy

As described by the NIH, a variety of agents can cause a person to have a reaction when eating shellfish. In the case of a true allergy, the allergen tropomyosin, common to all shellfish species, binds to the antibody IgE to trigger the release of inflammatory chemicals, resulting in mild or severe clinical symptoms. Substances consumed along with the shellfish, such as spices or chemical additives, may also trigger a true allergic reaction. Moreover, a person can also become allergically sensitized to shellfish without ingesting it, e.g., via exposure in the home or during processing in factories (per a 2016 review of studies in Allergo Journal International).

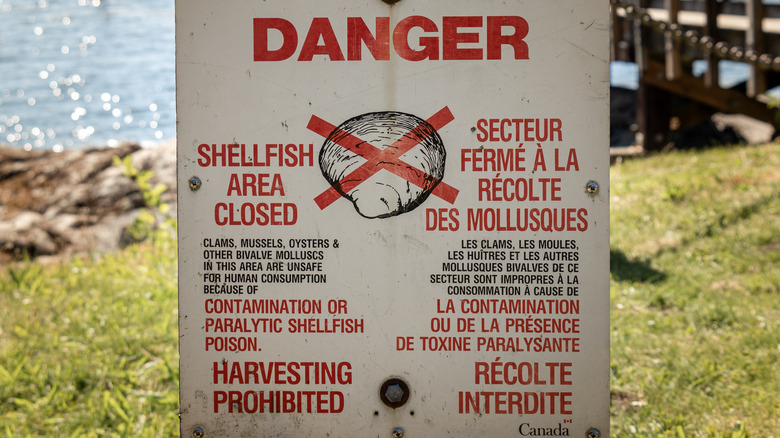

Apart from true shellfish allergy mediated by the immune system, shellfish reactions can be caused by various pathogens and toxins, reports the NIH. For example, the bacteria Vibrio, Listeria, and Salmonella are linked to shellfish reactions, whereas fish poisoning can result from ingesting shellfish contaminated with the neurotoxins ciguatoxin and saxitoxin. Domoic acid is another neurotoxin found in contaminated shellfish that can lead to permanent memory impairment, brain damage, and even death (via a 2020 study in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology).

Symptoms of shellfish allergy

In general, allergic reactions to shellfish occur within a few minutes (or hours) after eating or being exposed to shellfish, reports the Cleveland Clinic. Symptoms range from mild to severe, and can develop in different parts of the body. They may include common allergy symptoms such as hives, itching, eczema, and paleness, as well as swelling or tingling of the lips, face, tongue, or throat. If the airways are affected, some allergic people may experience congestion, wheezing, shortness of breath, coughing, or chest tightness. Others may get dizzy, feel lightheaded, or faint. Abdominal pain, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, and other gut problems may occur as well.

According to the Mayo Clinic, very severe allergic reactions to shellfish can trigger anaphylaxis, a widespread and potentially fatal reaction. Anaphylactic reactions can ensue within seconds to minutes after shellfish exposure. During an anaphylactic reaction, the heartbeat may speed up and blood pressure may fall, causing fainting or even shock. Other symptoms affecting the skin, respiration, and the gut are similar to the above general allergic reactions. Anaphylaxis can quickly deteriorate within 1 to 2 minutes, at which point the patient collapses, has seizures, stops breathing, and loses consciousness (via the Merck Manual). Emergency care must be given immediately to prevent death. Furthermore, a second round of symptoms may recur 4 to 8 hours after shellfish exposure or later. Though often milder than they were initially, these late-onset symptoms can lead to more severe outcomes.

Shellfish allergy diagnosis

Since shellfish allergy, like other IgE-mediated food allergies, is a major cause of life-threatening anaphylaxis, accurate and timely diagnosis is critical (per a 2018 study in Allergy, Asthma, & Clinical Immunology). Per the Mayo Clinic, a history of prior episodes of allergic reactions linked to shellfish exposure provides a clue, but allergy testing can confirm a diagnosis. An allergist may perform a skin prick test on the arm or upper back. Diluted shellfish proteins are dropped onto the skin, which is then pricked to allow the proteins to seep into the skin. After about 15 to 20 minutes, the appearance of a raised bump, or hive, indicates an allergic reaction. Another option is a blood test measuring the amount of IgE antibodies produced by the immune system when blood is exposed to shellfish proteins.

As described in a 2018 study in the Journal of Asthma and Allergy, an oral food challenge may be necessary for a definitive diagnosis of clinical food allergy. In a single-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge, the patient does not know whether the substance ingested is from shellfish or a placebo. The taste and smell of shellfish is concealed by mixing it with a carrier (substance that the patient tolerates) that is also used as the placebo. On separate days, shellfish and placebo are administered to the patient in progressively higher doses until a reaction occurs. The gold standard for diagnosing food allergy is a double-blinded challenge, in which both the patient and allergist are unaware of what is being tested.

Management of shellfish allergy

Complete avoidance of shellfish is the best management strategy (via the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology). Some common sources of shellfish components are fish stock, seafood flavoring, and sushi. Allergic diners eating out must be extra vigilant, as restaurant staff may be unaware of potential shellfish exposures from minor ingredients or nearby fumes. Fortunately, in the Unites States, the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA) of 2004 requires food manufacturers to clearly list in plain language any amount of crustacean shellfish (or any other major food allergens) on labels of packaged foods. However, only crustacean shellfish are regulated by FALCPA, and not mollusks. Also, as noted by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, warning statements (e.g., "May contain trace amounts of allergen (shellfish)") are not regulated by FALCPA; rather, they are voluntary.

Children can have a shellfish reaction at school or other places outside the home. Thus, policies and instructions for preventing food reactions and anaphylaxis should be a priority for schools and childcare centers. Due to strong cross-reactivity among crustacean shellfish, the management of a specific crustacean allergy should include avoidance of all crustaceans (per a 2011 study in Clinical and Translational Allergy). A more cautious strategy excludes all mollusks as well, as suggested by a 2016 study in Allergo Journal International. People with shellfish allergy may not be aware of the large variety of shellfish species, thus making mixed seafood dishes risky.

Treatment of shellfish allergy

For mild symptoms caused by allergic reactions to shellfish, the standard therapy is histamines and steroids, reports the NIH. For severe symptoms of anaphylactic reactions, an epinephrine injection is the first-line treatment and must be given immediately. Antihistamines, steroids, and IV fluids are given as a follow-up treatment.

When epinephrine is administered with an auto-injector outside of a medical setting, as described by the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the affected individual should promptly call 911 and alert the dispatcher of the need for additional epinephrine because severe reactions can recur. Adverse effects of epinephrine can occur, particularly in people with pre-existing conditions. Temporary anxiety, restlessness, dizziness, and shakiness are common, whereas abnormal heart rate, a heart attack, a spike in blood pressure, and fluid in the lungs are rare and typically related to dosing errors.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, allergic individuals should use an epinephrine injection without delay when experiencing shortness of breath, coughing, throat tightness, hives, swelling, vomiting, or diarrhea. If there is any doubt about the severity of a symptom, epinephrine should be injected regardless, as the benefit outweighs the risk of a potentially wasted dose.

Sources of shellfish to avoid

As described by the Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCI), people with shellfish allergy need to be attentive to accidental exposures to shellfish and cross contamination. They should stay clear of seafood platters and smorgasbords as well as seafood purchased from a market where possible cross contamination can occur between shellfish and other fish. Caution should be taken when eating foods contaminated with seafood via cooking and preparation (e.g., carryout fish and chips, commercial pizzas).

The popular arthritis supplement glucosamine is often made form the shells of crustaceans such as crab. Since the shellfish allergen is a protein and not found in the shell, the risk of a reaction is very low. Nevertheless, without proof of safety (no protein contamination), opting for a vegetarian alternative is advised. Although fish oil supplements are purified and also unlikely to contain shellfish allergens, medical advice is still warranted.

Due to a high risk of cross-contamination with shellfish, certain restaurants and cuisines should be avoided (via Verywell Health). Sauces and stocks featured in certain cuisines are often made from shrimp or imitation shellfish. Allergic individuals should always notify the server about their allergy. Some favorite fish soups and fish stews that may contain shellfish and should be avoided include Cioppino (fish stew), Etouffee (Cajun crawfish stew), and Gumbo (fish and shellfish stew). People with a shellfish allergy should also be mindful of non-food exposure from fish food, pet food, or calcium supplements made form oyster shells or coral.

Immunotherapy for shellfish allergy

Immunotherapy, commonly known as allergy shots, has been used for many years for the long-term treatment of allergic disorders (e.g., allergic rhinitis, allergic asthma, conjunctivitis) caused by airborne allergens, reports the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Immunotherapy works by exposing the immune system to gradually increasing doses of a specific allergen to induce tolerance to the allergen. As described by a 2018 review of studies published in the journal Children (Basel), food immunotherapy works by the same mechanism and is emerging as a promising alternative to strict food avoidance in the management of food allergy. Though currently experimental, oral food immunotherapy was shown to successfully desensitize 70-90% 0f patients to food proteins, primarily egg, cow's milk, and peanut.

Although evidence regarding food immunotherapy for shellfish allergy is very limited, a series of 3 case reports, as part of a 2022 multi-food oral immunotherapy trial published in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, supports the use of shrimp immunotherapy as an effective strategy to prevent severe allergic reactions. All 3 shrimp-allergic subjects in the trial were able to tolerate a maintenance dose of greater than one gram of shrimp by weeks 28-29 of the trial. From that point onward, the shrimp allergen must be routinely ingested to sustain desensitization for the long term. By week 30, 2 out of the 3 subjects completed a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge without any reaction. Despite the small sample size and lack of long-term follow-up, these findings warrant further investigation with larger trials.

The gut microbiota and food allergy

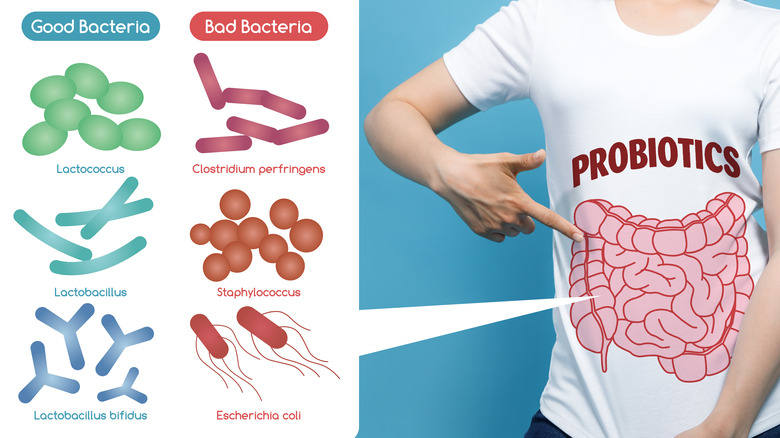

According to a 2021 review of studies in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, emerging evidence supports a major role of the gut microbiota in the development of food allergies, of which the vast majority are caused by a short list of foods that includes shellfish. It's widely recognized that changes in the levels or diversity of gut bacteria, or dysbiosis, is the primary driver of the increasing rate of food allergy.

The gut microbiota interacts with the immune system to promote and sustain oral tolerance to food allergens, explains a 2016 review of studies published in Current Opinion in Pediatrics. Dysbiosis early in life may increase the risk of developing food allergies. Several environmental factors are known to impact the gut microbiota and further the development of dysbiosis. These factors include Cesarian section delivery, formula feeding, low fiber/high-fat diet, antibiotic use (especially during infancy), gastric acidity inhibitors, disinfectants, pets, and farming lifestyle. Probiotics (live microorganisms) may potentially be used in the prevention and treatment of food allergy. By colonizing the gut and inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria, probiotics may enhance the function of the gut barrier in preventing the entry of unwanted food allergens into the body.

Prognosis of shellfish allergy

As noted in a 2020 study in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, the current standard of care for the clinical management of shellfish allergy is avoidance of shellfish and as-needed epinephrine injections for cases of severe allergic reactions. While immunotherapy for shellfish allergy is still in the investigational phase, results of small clinical trials are promising. The use of DNA vaccines is another novel approach being studied for the treatment of allergies, including shellfish allergy. Specifically, a vaccine made with a cloned gene for the shellfish allergen (tropomyosin) primes the immune system so that a protective immune response develops for the long term, thus promoting future tolerance to shellfish. The use of both immunotherapy and vaccines for the prevention and treatment of shellfish allergy is imminent.

Anyone with a shellfish allergy can expect to have it for life, reports the Cleveland Clinic. For those who love seafood, it can be quite frustrating. Nevertheless, the clinic advises people with shellfish allergy to keep a vigilant eye on possible shellfish exposures due to the risk of a potentially fatal allergic reaction.