Skin Cancer Explained: Causes, Types, And Treatments

According to the American Cancer Society, skin cancer is the "most commonly diagnosed" cancer in the United States. In fact, close to 10,000 people are diagnosed daily, and two or more people die of the disease every hour (per The Skin Cancer Foundation).

More statistics from The Skin Cancer Foundation found that while at least 20% of the population will have some form of skin cancer before they turn 70 there is an almost 100% survival rate if found early.

Furthermore, figures from the American Cancer Society credit advances in treatment for lowering the number of deaths by nearly 4% between 2015-2019.

As your body's largest organ, your skin is designed to guard your body against germs. Made up of water, protein, fats, and minerals, your skin also helps your body maintain the proper temperature. At the same time, the nerves in your skin enable you to feel sensations (via the Cleveland Clinic).

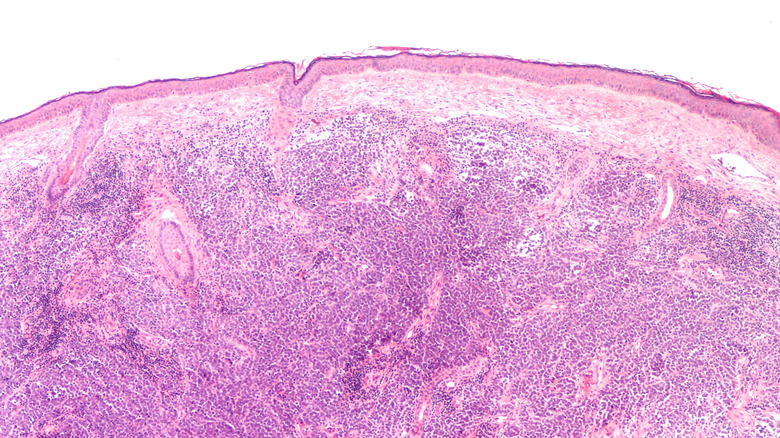

Your skin has several layers; the outermost is known as the epidermis and is where most skin cancer starts, according to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Skin cancer results from mutations in damaged skin DNA that causes accelerated growth that forms tumors (via the Skin Cancer Foundation).

The Mayo Clinic doctors recommend that a medical professional determine the cause of abnormal skin growths, as not all result from skin cancer. Let's take a closer look at all the types of skin cancer, as well as their available treatments and causes.

Causes of skin cancer

The sun gives off three types of light rays, ultraviolet A (UVA), ultraviolet B (UVB), and ultraviolet C (UVC). While UVC is the most dangerous, most of it gets filtered out before reaching Earth. Medical professionals believe that UVB is the ray that primarily causes harm. However, UVA also plays a significant role (via the NHS). Overexposure to ultraviolet rays that cause sunburn and blistering harms your skin's DNA, resulting in cancer (per the Cleveland Clinic). Sun lamps, tanning beds, and other artificial light sources also cause an increased risk of skin cancer development.

In addition to the sun rays, Cancer Treatment Centers of America report several other factors to consider when determining the possibility that you'll get skin cancer. These include age, overall health, gender, skin tone, and family history. The older you get and the more exposure you have to the sun's rays increases your chances of being diagnosed with skin cancer, especially the more you sunburn. Illnesses also boost your skin cancer risk, as does being born male. Additionally, the lighter your skin tone and the more moles on your body — along with any family history of the disease — cause an upsurge in your prospects of getting skin cancer.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AAD) reports that more than 2 million people in the United States are diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) annually. Furthermore, according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, BCC accounts for nearly 80% of skin cancer diagnoses in the U.S. The majority of those diagnosed with BCC are over the age of 50 (via MedlinePlus). When you're diagnosed with BCC, the cancerous cells are found in what is known as the basal cell layer. It is the bottom part of the top section of your skin, and is known as the epidermis.

BCC is most common in those with fair skin who fail to wear either sunscreen or sun-protective clothing while outside. Precursors to a BCC diagnosis include age spots, deep wrinkles, and skin discoloration (per the AAD).

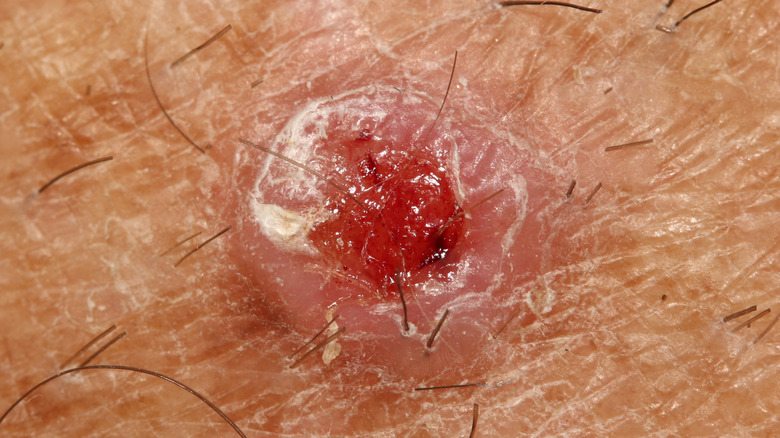

Those with BCC often notice non-painful bumps and lesions that look like scars on the parts of their body most exposed to the sun. Crusty, bleeding sores that don't heal are also common prior to diagnosis (via the Cleveland Clinic). And this type of skin cancer can also get into your nerves and bones, according to the AAD.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Statistics published by The Skin Cancer Foundation show that squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) affects nearly 2 million people annually, making it the second most common form of skin cancer in the United States. More than 15,000 people die from SCC every year in the U.S. SCC is also responsible for 90% of oral cancers and around a quarter of all lung cancers (per the National Cancer Institute). Similar to BCC, if caught early, almost everyone survives (via Moffitt Cancer Center).

SCC affects the middle section of your epidermis skin layer. Though somewhat slow-moving, doctors at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai warn that it is quicker than BCC and is therefore considered more likely to metastasize.

Though SCC looks different on everyone it affects, the Skin Cancer Foundation describes sores related to the disease as scaly, rough, red patches. The lesions look similar to warts but can crust, itch, and bleed.

According to the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, SCC primarily affects people with light skin, eyes, and hair. Severe sunburns and extended sun exposure further raise your risk of developing the disease. SCC most often appears on the face, ears, neck, hands, or arms of those diagnosed with this form of skin cancer.

Melanoma

According to the American Cancer Society, nearly 100,000 people get diagnosed with melanoma annually. Though that only makes up for approximately 1% of all skin cancer diagnoses in the United States, melanoma is responsible for "a large majority of skin cancer deaths." The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) puts the number of deaths yearly from melanoma at approximately 7,650 in the U.S.

The upper layer of your skin possesses cells known as melanocytes. Melanocytes give your skin its color by creating two types of the pigment known as melanin, called eumelanin and pheomelanin. According to The Skin Cancer Foundation, only eumelanin can protect you from the sun. It does so by darkening your skin. Those with less eumelanin are more susceptible to melanoma.

Doctors at the Mayo Clinic report melanoma is often caught through changing moles or discovering new ones. Most adults have an average of 10-40 moles, with most moles appearing either in childhood or after age 40. It is recommended that you have a medical professional check your moles to ensure they're not asymmetrical or have an irregular edge. Also, watch for size, shape, and color changes, and make an appointment if your moles suddenly itch or bleed.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCLs)

Annually, only six people per 1 million are diagnosed with Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), according to the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Furthermore, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), around 1,000 Americans receive this diagnosis annually, and approximately 20,000 live with the disease in the United States.

As part of a type of cancer known as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, CTCL affects the white blood cells in your skin, known as T cells or T lymphocytes. These cells are charged with helping your immune system. However, with CTCL, the T cells attack your skin, resulting in slightly raised or scaly round skin patches or tumors in your skin (via Mayo Clinic).

The Lymphoma Research Foundation reports two main types of CTCL, mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary Syndrome. MF is more common than Sézary Syndrome and presents as patches, plaques, or tumors. Sézary Syndrome looks more like an itchy, thin, red rash.

According to Johns Hopkins University, CTCLs are slow growing, and prognosis depends on the stage at which the cancer is discovered, along with the type and extent of skin lesions you have (via Leukemia & Lymphoma Society).

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare form of skin cancer diagnosed in one in 100,000 to one in 1 million people annually (via MedlinePlus). Of those with this form of the disease, only around 5% see it spread from its origin. According to the Cleveland Clinic, DFSP differs from other cancers in several ways. First, "DFSP appears to affect people who are Black more often than people of other ethnicities" (via the Cleveland Clinic). And, unlike previously mentioned skin cancers, it is not attributed to sunlight or UV rays. Moreover, DFSP affects your dermis or middle layer of skin, and this type of skin cancer is known to return after surgical treatment. Finally, those between the ages of 20-50 are most likely to be diagnosed with DFSP.

Appearing mainly on your arms, legs, and torso, the rough patches of skin or pimple-like lumps associated with DFSP also develop in areas of your body damaged by burns, scars, or tattoos (per the Cleveland Clinic).

DFSP varies depending on the cell makeup of the tumor; melanin-containing Bednar tumors appear dark in color, while Myxoid DFSP's include myxoid stroma, which is "an abnormal type of connective tissue." Giant cell fibroblastoma or juvenile dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans are named as such since the cells in the tumor are much larger than those in other tumors, and this type of DFSP is more likely to affect the children and teens (via MedlinePlus).

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC)

The American Cancer Society reports that approximately 2,000 people get diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) every year in the United States. MCC affects white seniors older than 70 about 90% more often than people of other races. The survival rate at five years is approximately 70%. Unfortunately, as the second most common cause of death related to skin cancer, MCC quickly grows and spreads (per the National Cancer Institute).

MCC originates in the cells in the top layer of your skin. Known as Merkel cells, they grow close to the nerve endings that allow you to feel touch. Like most other forms of skin cancer, MCC usually starts in sun-exposed skin (via National Cancer Institute).

However, according to the Cleveland Clinic, a weakened immune system can also cause MCC. This is due, in part, to the fact that 80% of those diagnosed with MCC have Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCP). MCP is a common childhood virus that doesn't cause symptoms in most who get it. Researchers are still trying to determine the connection between the virus and skin cancer.

Rapid growth is what causes alarm when it comes to the spots associated with MCC. Pimple-like in appearance, these marks don't usually hurt when touched (per The Skin Cancer Foundation).

The number of cases is steadily rising, and medical professionals at the Cleveland Clinic attribute the increase to improved testing and longevity.

Sebaceous carcinoma (SC)

Between 5-10% of skin cancers occur as eyelid tumors. Of those, approximately 1% are diagnosed as sebaceous carcinoma, making this type of skin cancer extremely rare (via the Cleveland Clinic). Most people with this type of skin cancer get diagnosed between the age of 60-80 and were born female. However, of those patients who received treatment early, nearly 80% survived over five years. The percentage drops to 50% once cancer metastases (per American Association for Cancer Research AACR).

SC forms in your skin's oil glands and is most often found on the eyelids (via the Mayo Clinic). It usually starts with a slow-growing, firm lump (via Stanford Health Care). Over time, it often turns yellow and, if not treated, could look like pink eye or a stye, and additional growth could lead to eyesight issues. If SC appears anywhere else on your body, it presents as a slow-growing pink or yellowish lump and could bleed. Like most other forms of skin cancer, it results from spending too much time in the sun without protection. Other contributing factors include a weakened immune system and previous radiation therapy.

Unfortunately, SC is known to be aggressive and often returns after treatment, according to the American Academy of Dermatology Association.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) is used to kill skin cancer cells and, because of newer, more targeted treatments, is generally not the first line of defense used. Additionally, the American Cancer Society reports that chemo isn't very effective when used for melanoma and only serves to shrink tumors in a small group of people.

Doctors at Moffitt Cancer Center use chemo for nonmelanoma skin cancers as it helps eliminate residual basal and squamous cells that medical professionals cannot remove by other means.

The two most common types of chemo used for skin cancer are topical and systemic. Topical chemo is applied directly onto the skin in the affected area and is designed to remove precancerous cells and those that haven't spread (via Moffitt Cancer Center). Due to the localized nature of this treatment, side effects only affect the area treated and include burning or itching and redness or a rash. Your skin may also feel sore or tender to the touch (per Cancer Center Treatment Centers of America).

If your skin cancer has spread, doctors at Moffitt Cancer Center use systemic chemotherapy to slow the spread. According to Cancer Center Treatment Centers of America, this type of treatment comes with many common side effects, including digestive issues, hair loss, and immune suppression. However, these issues tend to dissipate once you finish treatment.

Surgery

Surgery is one of the most common ways to treat skin cancer. However, the procedure you undergo depends on the kind of skin cancer you're diagnosed with, its location, and how far along it has developed (via Cancer Research UK).

Most skin cancer diagnoses begin with a biopsy. This procedure requires your doctor to numb the affected area and remove the diseased tissue along with some healthy tissue. This specimen is sent off to be examined, so your doctor knows what to do next (per Cancer Research UK).

Medical professionals at Johns Hopkins University remove smaller, less complicated skin tumors using cryosurgery or curettage and electrosurgery. During cryosurgery, your doctor sprays the area with liquid nitrogen to freeze and destroy the diseased cells. It takes about two weeks for the dead tissue to fall off. When curettage and electrosurgery are used, the doctor scrapes away as much cancerous tissue as possible and then uses an electric current to kill off any remaining cells and control bleeding.

During Mohs surgery, the doctors at NYU Langone numb the affected area and remove a thin layer of tissue. It is then analyzed, and if any cancer remains, the doctor goes back in to take another layer. Mohs keeps scars small and reduces the need for additional surgery.

If your doctor thinks your cancer has spread, you may undergo a lymph node biopsy wherein a sample or an entire lymph node gets removed for examination. Should cancer be found, additional steps will be taken (per NYU Langone).

Radiation

When medical professionals at SERO use radiation to treat cancer, they utilize invisible rays of high-energy radiation to damage the DNA in the affected cells, killing them off. According to UCLA Health, radiation causes cells to be unable to multiply. As a result, your body eliminates the dead, diseased cells, and any healthy cells affected heal once your sessions are complete.

External beam radiation therapy is the most common form of radiation used to treat skin cancer. Your doctor uses a specialized machine to emit the waves into the tumor in hopes of avoiding healthy tissue and organs that surround it. To ensure the best outcome, you must be treated daily for weeks. However, radiation is generally painless, and sessions usually last less than an hour (via UCLA Health).

Radiation is often used on its own for skin cancer that hasn't spread. However, doctors at SERO also use radiation in conjunction with other treatments to improve a patient's outcome.

Since radiation isn't exact (at 90% effective) medical professionals at the Skin Cancer Foundation generally reserve radiation for skin cancers that cannot be treated surgically.

According to the American Academy of Dermatology Association, side effects associated with radiation include itchiness, redness, blistering, and peeling. Cancer Council NSW advises patients to ask for creams to ease discomfort. Side effects often don't appear until after you've finished radiation therapy, but usually improve in six weeks.

Targeted therapy

AIM at Melanoma uses the term targeted therapy to describe medications specifically designed to attack molecules that help cancer cells spread. Samitivej Hospital further explains that, unlike chemo, the drugs used in targeted therapy don't destroy healthy cells. Additionally, doctors at Penn Medicine state that while chemo only kills the cancer cells you currently have, targeted therapy makes it so new cancer cells cannot develop. Regarding skin cancer, targeted therapy is used primarily for melanoma (per AIM at Melanoma).

Also, studies reported by Samitivej Hospital show that targeted therapy is much more effective at getting rid of melanoma than chemotherapy. Chemo has a 30% success rate, and targeted therapy is 80% successful. However, not everyone is a candidate for targeted therapy.

Medical professionals at Penn Medicine use one of three types of targeted therapy to treat your skin cancer. BRAF inhibitors help with melanomas associated with a mutation in the BRAF gene. Along a similar line are MEK inhibitors that work to target the protein in the BRAF gene. KIT inhibitors are used for more rare types of melanoma that have specific KIT gene mutations

Side effects related to targeted therapy depend on the medications you are given and often include rashes, dry skin, joint pain, and hair thinning. However, reactions tend to decrease when BRAF and MEK inhibitors are used together (per ASCO).

For best results, doctors at Penn Medicine often recommend using targeted therapy in conjunction with other treatments.

Topical therapy

Topical therapy treats basal and squamous cell carcinoma using creams and ointments that you apply directly to your skin in the affected area. Topical therapy kills cancer cells that haven't spread to your lymph nodes (via Mercy Health).

Cancer Council NSW offers two types of topical therapy for skin cancer. Imiquimod is an immunotherapy cream designed to make your immune system kill cancer cells. Imiquimod works for sunspots and BCC. You apply the cream nightly, five days a week, for six weeks.

The other topical treatment offered by Cancer Council NSW is a chemotherapy drug called 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which also gets dispensed as a cream. Like Imiquimod, 5-FU treats sunspots. Doctors also prescribe 5-FU for SCC, which works best on the face and scalp. Medical professionals recommend you use 5-FU twice a day for two to three weeks.

The Skin Cancer Foundation puts the success rate of both types of topical treatments at 80-90% effective. This rate is due, in part, to the fact that with topical therapies, no tissue gets removed for microscopic examination. Therefore, there's no way to know if the cancer is completely gone once you finish your course of treatment.

Many patients request topical therapy because it's convenient and scarring is minimal (per Mercy Health). However, blisters, peeling, and scabbing commonly result in many patients stopping their treatment early (via The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology). According to the Cancer Council NSW, side effects diminish within a few weeks of finishing treatment.

Immunotherapy

The American Cancer Society defines immunotherapy as using medications to stimulate one's immune system to better recognize and destroy cancer cells in the body.

Immunotherapy is most often used to treat people with advanced basal or squamous cell skin cancer (per American Cancer Society). Nearly half of those treated with immunotherapy were still alive after six and a half years, and more than one third of those who survived hadn't had their cancer worsen (via Dana-Farber Cancer Institute).

According to Healthline, doctors prescribe three types of immunotherapy drugs. The most common of which is known as a checkpoint inhibitor. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center describes this type of immunotherapy as blocking immune checkpoints by blocking the molecule that regulates T cells. T cells look for and kill tumors.

Another type of immunotherapy, cytokines, boosts your immune system's response to your cancer. It is often prescribed after you've undergone melanoma surgery to help lower your chances of recurrence. Cytokines also benefit those who haven't responded well to other treatments (per Healthline).

Another way doctors try to trigger your immune system to fight your cancer is by using oncolytic virus therapy. This type of immunotherapy uses modified viruses to infect and ultimately kill cancer cells. These viruses also prompt your immune system to attack the cancer cells (via Healthline).

Side effects are generally flu-like in nature. However, the American Cancer Society reminds you that immunotherapy suppresses your immune system and can lead to other serious health issues.