Myths You Should Stop Believing About Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is one of the multiple bacterial infections that can be transmitted by ticks. According to MedlinePlus, people get Lyme disease when they're bitten by a tick infected with the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. However, the infection isn't passed as soon as the bite occurs. A tick must be attached to a human host and feeding for at least 36 to 48 hours to transmit Borrelia burgdorferi.

The first symptoms of Lyme disease often manifest within a few days after being bitten by an infected tick. For many, the first noticeable symptom is a rash around the tick bite. Lyme disease often causes a distinct rash that looks like a bull's-eye with the tick bite at the center and a circular rash around the bite. Some people also get flu-like symptoms, including headache, chills, fever, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, and aches and pains, especially in the joints.

When Lyme disease is diagnosed and treated quickly with antibiotics, the infection usually resolves. However, some people find that it takes months to recover, and, in rare cases, chronic illness can develop. As Stanford University's Kris Newby highlighted in a feature for Vox, Lyme disease is often both misunderstood and misdiagnosed. Unfortunately, these problems created several persistent myths about Lyme disease. Even though many of these myths have been debunked through scientific research, they continue to spread — but we're here to set the record straight.

Myth: Lyme disease doesn't cause chronic illness

The biggest Lyme disease controversy centers on post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS), a chronic illness often called "Chronic Lyme Disease" (CLD). A paper published in the Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences states that 10-20% of patients who get infected with Lyme disease will have long-term symptoms after initial treatment. However, the difficulties with diagnosing and treating Lyme disease have led to a deep divide within the medical community. Some believe that the lingering symptoms are caused by an active, persistent Lyme disease infection. Others believe that they are the manifestation of a post-infection autoimmune condition. Still others believe that the symptoms are unrelated to Lyme disease and that PTLDS/CLD doesn't exist at all. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognizes PTLDS as a chronic illness, but acknowledges that a lot doctors, scientists, and researchers don't know about it.

Regardless of the medical community's views on PTLDS/CLD, thousands of people in the United States are struggling with the chronic illness, per a study published in BioMed Central Public Health. And it has a major impact on their well-being. One study found that people diagnosed with PTLDS experience a poorer quality of life and greater symptom severity than people with other chronic illnesses.

Myth: Lyme disease always causes a bull's-eye rash

Because Lyme disease often causes a very distinct bull's-eye rash, this symptom is considered one of the "hallmarks" of the infection. Per the Mayo Clinic, this rash can show up as soon as three days after someone is bit by an infected tick, but it may not show up until as late as 30 days after the bite. And sometimes the rash doesn't appear at all. Dr. Neil Spector, a cancer researcher who contracted Lyme disease in the 90s, told CBS News that research estimates 40-50% of people who contract Lyme disease don't get a rash at all or get a rash that doesn't look like the classic bull's-eye rash. According to the CDC, a rash caused by Lyme disease can present in several different ways, and often looks very different on darker skin.

Unfortunately, Spector said to CBS News, many doctors look only for the classic bull's-eye rash and may miss cases of Lyme in which it never appears. As a result, many people don't know they have Lyme disease until they've had it for months or even years. For this reason, it's important for doctors and patients to understand the other symptoms associated with a Lyme disease infection in case a rash never manifests.

Myth: You'll know you have Lyme disease from your symptoms

Other than the bulls-eye rash that may or may not appear around the tick bite, Lyme disease doesn't have any unique symptoms that distinguish it from other illnesses, according to WebMD. The earliest symptoms of Lyme disease are often fatigue, headaches, muscle aches, and a fever. All of these symptoms could also be caused by a simple cold or the flu, and most people experiencing them probably wouldn't think that Lyme disease was the most likely explanation.

A few weeks after being bitten, some people with Lyme disease develop additional symptoms like shortness of breath, dizziness, increased heart rate, nerve pain, joint pain and swelling, tingling in their hands and feet, and problems with their memory. If the infection is left untreated for long enough, Lyme disease can even cause neurological and cardiac problems as well as joint issues that mimic arthritis, according to UpToDate.

Since the symptoms are wide-ranging and similar to those of other illnesses, it's nearly impossible to recognize Lyme disease based on its symptoms. Indeed, people may not suspect Lyme at all unless they find a tick on them or remember getting bitten at some point.

Myth: If you didn't find a tick bite, it's definitely not Lyme disease

Believe it or not, it's common to get a tick bite without ever knowing about it. According to MedlinePlus, the ticks that spread Lyme disease are usually no larger than the size of a pinhead. They're so tiny that you might not see them on your skin even if you're looking for them during a tick check after a hike.

Dr. Andrea Gaito, a rheumatologist, told Women's Health that another reason ticks often go unnoticed is they like to bite warm, damp places on our bodies — like behind the knees, under the breasts, or even in the groin area. Ticks also like to hide in hair and often bite the scalp. All of these places are hard or impossible to thoroughly examine on your own. So, a tick bite can go completely unnoticed, especially if a rash doesn't develop.

Dr. Gaito said that it's quite common for people to have Lyme disease for a long time without knowing it because they never knew they were bitten by a tick. The longer the disease goes undiagnosed, the more likely it is for chronic Lyme disease to develop.

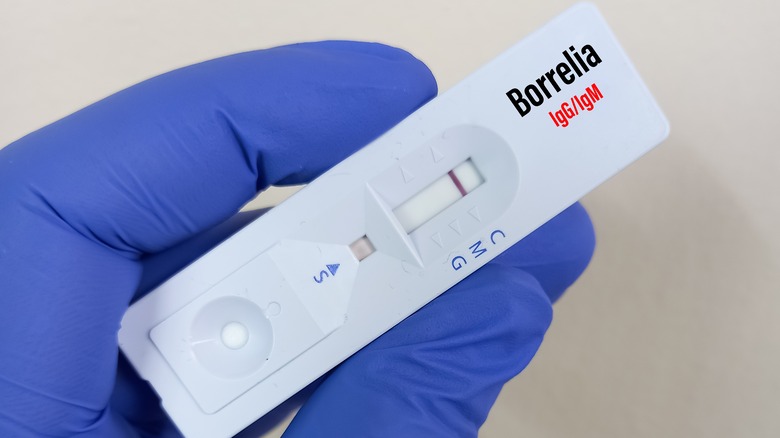

Myth: A negative test means you don't have Lyme disease

As Columbia University's Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center explains, all of the tests currently available for Lyme disease have significant flaws. Blood tests that look for the antibodies that fight Lyme disease can give false positives and false negatives. It takes the body about two or three weeks to develop Lyme antibodies, and even longer for those antibodies to build up to a detectable level. Consequently, blood tests that detect antibodies often give a false negative within the first few weeks of infection, the crucial time period for treating Lyme.

Additionally, the presence of antibodies doesn't always mean that someone has an active infection. Antibodies for Lyme can remain at detectable levels for months or years after an infection, leading to a false positive. If the blood test isn't specific enough, proteins that are similar to the ones produced by Lyme antibodies can also trigger a false positive.

There are blood tests that detect the presence of the actual bacteria that causes Lyme disease rather than the antibodies. However, these tests are often inaccurate as well. The bacteria doesn't stay in the blood for very long. So, if a blood test for the bacteria is performed too long after the initial infection, it will give a false negative. Unfortunately, no matter what kind of test is performed, the results are not a reliable way to determine whether or not someone actually has Lyme disease.

Myth: If you're sick after a tick bite, it's definitely Lyme disease

If you do happen to find a tick on your body and get sick within a few weeks, it would be logical to assume you have Lyme disease. However, Lyme disease is far from the only illness that can be transmitted by ticks. According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), many ticks are infected with multiple pathogens, many of which can be transmitted to and cause disease in humans.

Yale Medicine's tick-borne illness experts state that the same ticks that spread Lyme disease may also be infected with Powassan virus, babesiosis, or anaplasmosis, among others. All of these tick-borne illnesses can cause fever, chills, headaches, and muscle pain, which are also symptoms of Lyme disease. Different tick-borne disease often present with similar symptoms (via the CDC), making it difficult to determine which tick-borne illness a person has based on symptoms alone. It's also common for people to get infected with multiple tick-borne illnesses at once, which complicates both diagnosis and treatment (via (NIAID).

The bottom line is that sickness after a tick bite does not necessarily mean you have Lyme disease, but it does mean that you should see your doctor and get evaluated for tick-borne illnesses.

Myth: Only deer ticks transmit Lyme disease

You may have heard that only one kind of tick — the deer tick — can carry Lyme disease. This is technically true, and that kernel of truth leads many to assume that only one species of tick carries Lyme disease. And that's not true. According to the Global Lyme Alliance, "deer tick" is the commonly used name for black-legged ticks. There are two varieties of black-legged ticks: Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus. Ixodes scapularis are more common on the east coast and in the northern states in the center of the U.S., while Ixodes pacificus only exist on the west coast, per Johns Hopkins Medicine. It's important to note that both varieties of black-legged ticks can carry the bacteria that causes Lyme disease and transmit that bacteria to humans.

Additionally, deer tick isn't really an accurate name for black-legged ticks. Though deer do frequently carry these ticks, they're also carried by several kinds of animals including mice, raccoons, squirrels, and even birds and lizards, per The Humane Society. However, the name "deer tick" led many to believe that deer are solely responsible for the spread of ticks that carry Lyme disease. This created a fundamental misunderstanding of how Lyme disease spreads, where it spreads, and who's at risk.

Myth: You can only get Lyme disease on the east coast

A paper published in the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine states that researchers from Yale University identified what they believed to be a previously unknown form of arthritis in 51 people who all lived in the same three towns in Connecticut in the 1970s. As they studied the "arthritis," they discovered that it was actually a tick-borne infection with a wide array of symptoms. For many years, per the Yale School of Medicine, Lyme disease seemed isolated to the northeast U.S.

However, in the past few decades, Lyme disease has spread rapidly through the United States. According to a paper published in the Journal of Medical Entomology, cases have been increasing down the east coast, throughout the Midwest, and even on the west coast. This is due to a habitat expansion of the ticks that carry Lyme disease. In 1998, black-legged ticks were found in 30% of U.S. counties. In 2016, they were found in 45.7% of U.S. counties. However, the ticks are still not found in every state. The black-legged tick remains most prevalent on the east coast, with rising numbers in the middle of the country and the west coast. All told, the ticks are found in 37 states. Researchers theorize that this habitat expansion has occurred because climate change created milder winters across the U.S. and changed migration patterns of small mammals and birds, which brought black-legged ticks to new areas (via Yale School of Medicine).

Myth: You only need to worry about Lyme disease in the summer

Many people might assume that ticks, like other bugs, can't survive or thrive in the freezing temperatures of winter, but new research is proving that assumption false. Smithsonian Magazine reported that research conducted by scientists at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia found that 79% of ticks infected with the bacteria that causes Lyme disease survived in freezing temperatures. Their research also found that infected ticks became more active once temperatures rose above 37 degrees Fahrenheit. With winter temperatures increasing around the globe, the research suggests that ticks infected with Lyme disease could be active during the winter.

Theresa Crimmins, a biologist from the University of Arizona, told the Guardian that climate change is also expanding the tick season. She stated that ticks are now active earlier in the spring and later into the fall, lengthening the amount of time people are at risk for contracting Lyme disease.

Myth: You can only get Lyme disease in the woods

When Nicole Greene was first diagnosed with Lyme disease, she thought, "I'm not an outdoor person, there's no way I have that," CBS News reported. Like Greene, many people believe that if they're not "outdoors people" or never go in the woods, then they won't get Lyme disease. However, several common activities that aren't typically considered outdoorsy can increase your risk of encountering a tick carrying Lyme disease.

According to The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, the majority of people who have Lyme disease encountered the tick that infected them quite near to their own homes. Doing yard work, gardening, and playing in the yard all put you and your family at greater risk for tick bites. Pets that spend time outdoors can also bring in ticks when they come back inside. So, it's possible to get a tick bite without spending much time outside or going into wooded areas.

Less than a quarter of the people who get Lyme disease pick up a tick while doing activities away from their homes. Outdoorsy activities like camping, hiking, hunting, and fishing increase the risk of getting bit by a tick carrying Lyme disease (per Nemours Children's Health). However, recreational activities like horseback riding, golfing, and playing field sports are also high-risk. But the bottom line is that anyone who lives in a place with a significant population of black-legged ticks is at risk for Lyme disease, even if they don't spend much time outside.

Myth: Lyme disease is rare

Between 1992 and 2006, the CDC reported only 248,074 cases of Lyme disease in the United States. However, by 2010, research estimated that between 296,000–376,000 cases of Lyme disease occurred every year (via Emerging Infectious Diseases).

Currently, the CDC estimates that about 300,000 people get Lyme disease each year. However, the agency acknowledges that there's no way to get a clear number of how many cases actually occur. Some research has estimated case numbers based on insurance claims, while others have generated estimates based on diagnoses. As the CDC points out on their site, these numbers may still be inaccurate due to the fact that doctors often give a diagnosis of Lyme disease based on a patient's symptomatology rather than test results because there are so many issues with the tests for Lyme disease. Regardless of the actual number of cases, the estimated number of cases per year shows that Lyme disease definitely isn't rare anymore.

Myth: Lyme disease is easy to treat

Unfortunately, getting successfully treated for Lyme disease is just about as difficult as getting diagnosed because there is no standard treatment protocol, per a paper in the medical journal Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. Though doctors generally agree that antibiotics are effective when Lyme disease is diagnosed within a few weeks of infection, recommendations for the course of antibiotics vary. Most commonly, though, someone can expect to take antibiotics for between 14 and 21 days, though depending on the medication the stage of infection, the course could be as little as seven days or as many as 28 (via Medscape). Though many doctors prefer doxycycline, some prescribe amoxicillin or cefuroxime (per Columbia University).

Additionally, the unreliability of blood tests for Lyme disease makes getting a definitive diagnosis within the effective treatment period difficult. If a diagnosis isn't made within a few weeks, the disease progresses and becomes harder to treat. The guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America state that a four-week course of antibiotics is the recommended protocol for late-stage Lyme disease. Antibiotics may be administered orally or intravenously if oral antibiotics don't resolve symptoms. However, according to a paper published in Frontiers in Medicine Infectious Diseases, antibiotics won't work for everyone, and there is no agreed upon treatment protocol for antibiotic-resistant cases. And though early-stage Lyme disease is relatively easy to treat with a course of antibiotics, cases that go undiagnosed or are resistant to antibiotic treatment are exceedingly difficult to treat.

Myth: Antibiotics always cure Lyme disease

Research funded by NIAID has shown that antibiotics are highly effective for the majority of people who contract Lyme disease. Even people with more complicated cases of Lyme disease often recover after taking antibiotics for three to four weeks. However, some people will not respond to antibiotic treatment, regardless of how far the disease has progressed. These patients get diagnosed with post-treatment Lyme disease (PTLD).

Though long-term antibiotic therapy was commonly prescribed for PTLD for many years, NIAID's research now shows that prolonged use of antibiotics does not improve PTLD symptoms. In fact, the CDC states that long-term antibiotic treatment can be harmful and even fatal.

The Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Center states that patients who do not respond to antibiotic treatment need to be treated based on their individual symptoms. These people should seek out a doctor who specializes in Lyme disease and specifically PTLD. Unfortunately, the PTLD diagnosis is still highly controversial, and many doctors may not have adequate knowledge to treat it. So, people who don't respond to antibiotic treatment often don't get the care they need.

Myth: Alternative medicine treatments are effective for Lyme disease

When antibiotics don't work for Lyme disease, many people might turn to alternative, more natural treatments. Indeed, a survey of people with Lyme disease conducted by LymeDisease.org found that many report getting a lot of relief from alternative treatments. However, the Mayo Clinic stresses that antibiotics are the only evidence-based treatment for Lyme disease, and that alternative treatments can be dangerous as well as ineffective. An investigation by Bloomberg found that some alternative treatments were linked to "dozens of reports of significant harm, including several deaths."

Unfortunately, one study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases found that natural and holistic alternative treatments are heavily marketed to people with Lyme disease. The study also found that the treatments being advertised as effective treatments were not backed by scientific evidence. The authors concluded that many people with Lyme disease, especially those who experience persistent symptoms, are drawn in by unproven alternative treatments because of negative experiences with and limited symptom relief from conventional medicine.

The bottom line with alternative treatments is discernment and the supervision of a good doctor. People experiencing persistent symptoms may find significant symptom relief from alternative treatments. However, no alternative treatment should replace antibiotic therapy or be undertaken without a doctor's advice.