Surprising Things About Men's Bodies People Used To Believe

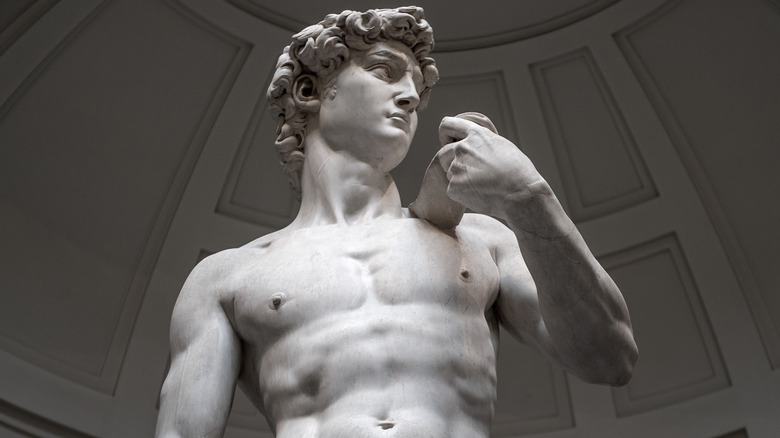

Human beings have been studying their own anatomy since the earliest days of civilization, with the ancient Egyptians first describing the practice of medicine, and the ancient Greeks the first to use scientific techniques like dissection, as a report published in Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal demonstrated. But as you might imagine, understanding the complexities of the human body is a slow process when you don't have any textbooks to help (because they hadn't been written yet). So we shouldn't be surprised that, for example, the heart used to be considered the source of all body heat. Even today, we don't have everything figured out; in fact, a new body part was discovered within the last decade (via UVA Health).

Since early anatomists considered the male body to be sort of the standard model, and women's bodies were viewed as a mysterious, "imperfect" approximation (per Standford University), it seems appropriate to survey the errors that were made despite the extra attention being paid. But keep in mind that not all strange conceits about the male body date back to the dawn of civilization. Some are much more recent and are believed in some quarters even today.

Underwear has been blamed for male fertility issues

There's a reason the male body is designed with the testes outside of the abdomen: Sperm production goes down as heat goes up. Letting the male gonads hang out actually keeps them 4 to 6 degrees cooler (via NPR). Given that, doesn't it seem reasonable that tight underwear would counteract nature's cooling system, pressing the family jewels up against the body the way they do?

Well, some research has supported this concept, like one study that found higher sperm counts in men who wore boxers compared to other underwear types. Countless "Boxers or Briefs?" headlines later, switching to the former has become easily followed advice for men looking to tilt the odds of conception in their favor.

However, a closer look sheds doubt on the idea, reports NPR. According to one of the study authors, the lower sperm counts they found among the non-boxer wearers were still within healthy levels. And another study found underwear made no significant difference in sperm count, nor the time it took for a couple to get pregnant. Stressing over underpants is may just be a waste of energy. And "couples are already stressed out enough when they're trying for a pregnancy," said Germaine Louis, one of the authors of that study.

You know what they say about big feet

How big is big enough and how small is too small? When it comes to penile length, men don't seem to have a good sense of the normal range or where they fit into it. Research shows that as many as 68% of men wish their penis was larger, and that most men think the average length of an erect penis is 6 inches. However, the actual average is more like 5 inches, according to a report in the Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. In one study of 67 patients who came to a clinic seeking treatment for a "short penis," none of them were actually outside the normal range.

This concern over length, and a lack of accurate comparisons, may be one reason for the persistent canard that the size of the male member is reflected in the size of his feet, hands, or other extremities. It may seem like a convenient way to compare stats, but there's no truth to it. In a study published in BJU International, urologists compared both penis length and shoe size among 104 male patients, and found there was no statistical relationship between the two.

Conception was a sticky puzzle for millennia

The facts of life that every schoolchild learns today were a matter of great mystery and debate for the deepest thinkers of previous centuries. A big part of the puzzle was how much each parent contributed to the conception of their child. To our agriculturally-oriented ancestors, it seemed reasonable that a man's semen was a type of seed, which took root and grew in the woman's body. But if that was the case, why did the offspring resemble both parents?

Hippocrates concluded that both men and women produced semen, which was secreted by all parts of the body. The two types — which contained miniature versions of all body parts — mixed to create new life. Aristotle challenged this theory, deciding that blood was the source of semen. In his view, the male's semen carried information and triggered conception, while the female's "passive" reproductive fluid provided the material to form the developing fetus, explained the Ancient Philosophy and the Classic Tradition journal.

With the invention of the microscope in the 17th century, the first observations of living sperm were a startling game-changer, reported the Smithsonian. But even then, attempts at explanation seemed to recapitulate previous arguments. "Preformationists" argued that sperm contained complete pre-formed humans. "Epigenicists" argued that both parents contributed material to create their offspring. The latter viewpoint was validated as improved observations in animals showed sperm and egg interacting, and organs developing gradually in embryos.

'Manustupration' was considered a major health threat

Okay, so it's not something you want to be caught doing during a Zoom meeting. But these days, most people consider engaging in some self-pleasure to be a harmless, if best kept private, endeavor.

Not so during the Victorian age, according to Mimi Matthews, author of "A Victorian Lady's Guide to Fashion and Beauty." Writing for Bust, she explained that anti-masturbation sentiment reached a fever pitch in the 19th century. Medical authorities of the day were fond of quoting an older medical tract which claimed that men who masturbated (or "manustuprated," as it was also called) risked everything from lethargy to epilepsy to loss of sight, paralysis, and "all kinds of painful affections."

One medical journal of the day declared that the so-called "solitary vice" produced loss of appetite, indigestion, clammy hands (!), inflammation of the brain, heart palpitation, palsy, and insanity. Physicians trotted out case studies of men who had been reduced to miserable living death by their seeming lack of self control. Schoolboys in particular were warned against indulging. Prayer, exercise, and suspect patent medicines were available to help kick the habit.

People believed men's bodies were better versions of women's bodies

To some thinkers in the ancient world, the way to explain the physical differences between men and women was to argue that female genitalia were an inside-out version of male genitalia. As described by historian Thomas Laqueur in his book "Making Sex: Body and Gender From the Greeks to Freud," this so-called "one-sex" model considered the male body to be the perfected human form, and the female body a "lesser" version. Patriarchy much? On the plus side, this did support the idea that men and women experience similar sexual desire and pleasure, since they essentially have the same sex organs (via Los Angeles Times).

In contrast to that is the two-sex model, which held that male and female sex organs are not different versions of the same thing, but are in fact fundamentally different. This may sound to contemporary ears like a more reasonable take. But perhaps not surprisingly, it's also been used to make questionable claims about the female body, like denying that women feel sexual passion.

In her book "The One-Sex Body on Trial," scholar Helen King explains that the two-sex model is an ancient conceit as well. For example, Hippocrates wrote that male and female flesh are essentially dissimilar, with women's bodies being softer and spongier (via Bryn Mawr Classical Review). Yeah, eye roll, but don't feel too superior. Even today science tends to define sex in binary terms, though some biologists tell us that's an oversimplification (via Scientific American).

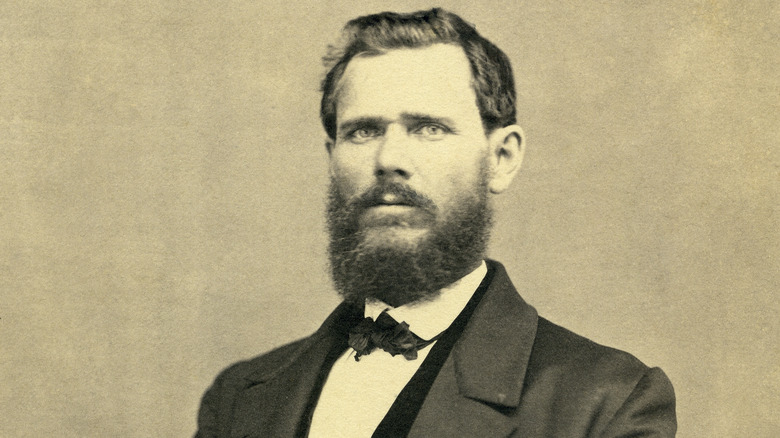

Beards were once a sign of racial superiority

Shaving has been the norm for men in the Western world since the days of the ancient Greeks, who felt that a clean chin brought men closer to the eternally youthful gods (via Esquire). Nevertheless, the trendiness of beards comes and goes.

In the 19th century, the beard became a signifier of the physical and moral superiority of, you guessed it, white European ancestry, reported Bustle. Races that were perceived as unable to grow significant facial hair were considered deficient in other areas. According to "The Philosophy of Beards," an 1854 manifesto, "the absence of Beard is usually a sign of physical and moral weakness."

In the United States, whiskers made a comeback in the mid-19th century after the previous decade's preference for shaving (not many beards among the founding fathers). Part of the reason, reported The Atlantic, was a growing discomfort among white males with going to the barber — who, for various cultural and historical reasons, was usually African-American. Since at that time shaving one's own beard was a difficult, painful, and dangerous operation involving a straight razor, men opted to let their facial hair grow wild. Ironically enough, what began as racial phobia and a fear of self-injury was transformed into a statement of tough-guy masculinity and dominance of "inferior" races.

The ancient Greeks considered males to be hot and dry, and females to be cool and wet

Medical theory in the time of Hippocrates — and for centuries to follow — was largely about bodily fluids, especially the "four humors" (blood, phlegm, and two kinds of bile), whose mixing were said to produce all sorts of physical and mental effects (via Britannica).

This framework included the belief that the male body was hotter and dryer than the female body. In fact, the higher moisture level in the female body was considered to be the reason for menstruation, as a way to rid of the excess fluid. Men were believed to be protected from some diseases because they lacked the higher moisture that women were purportedly burdened with. And the greater heat of the male body not only obviated the need for menstruation, according to Aristotle, it was also the reason that men were able to produce semen. He believed that the higher temperature of a man's body heated the blood to produce seminal fluid, a task not possible in a woman's colder corpus, as the journal Clio, Women, Gender, History explained.

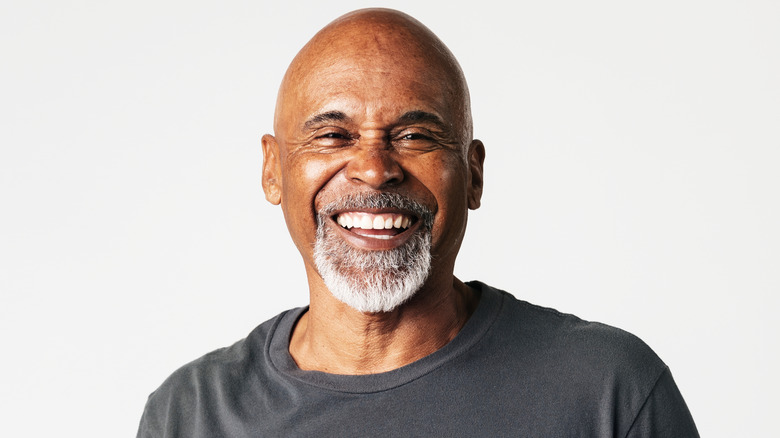

Baldness has been considered a sign of virility

On the face of it, this thinking seems like a worthwhile tradeoff: High testosterone levels produce a stronger sex drive but cause a man to lose his hair at a younger-than-average age. It's a modern interpretation of a purported link between baldness and virility that's been around since the days of Hippocrates and Aristotle. Sadly for the generations of bare-headed men who probably worked hard to keep the idea alive, baldness is not an indicator of elevated male hormone levels.

There is a connection, though, which was first discerned scientifically in 1960, when a researcher found that men who'd been medically castrated as boys did not show any signs of male pattern baldness, while a group of other men the same age did. This seemed to suggest that testosterone is the culprit for hair loss in men. But it turns out that the amount of testosterone doesn't matter; some men have genes that make their hair follicles sensitive to testosterone in any amount. Understanding how that works may one day lead to a way to reverse hair loss (via BBC).

Ancient Egyptian men liked to wear makeup

If you were a dude, especially an upper-class one, living Egypt during the age of Pharaohs, you wouldn't dream of leaving the house without fixing your face. For the men of Egypt, it was only natural to adorn their body with oils, fragrances, cosmetics and other treatments (via How Stuff Works).

Some of this was a practical concern. A treatment of oils or animal fats would offer protection from the harsh Egyptian sun. Laborers counted on massage oil to moisturize their skin and soothe their tired muscles; in at least one case, when workers weren't supplied with the oil they'd been promised, they went on strike. Lotions might be scented; other times, Egyptians might place dried fat on their head which, as it melted in the heat, released fragrances of flowers and spices. Dark eye makeup helped protect the eyes from bright sunlight and flies, but was also a fashion statement that recalled the face of the sun god Horus (via Byrdie).

Upper-class men also tended to shave their heads, or keep their hair short, and they wore wigs of human hair as a way of showing their power over others. Priests removed all of their body hair, including their eyebrows (via JSTOR Daily).

Are men's brains different than women's brains? Think again

As years and years' worth of stand-up comedy routines would testify, men and women often behave differently. But are those differences hardwired? Are the male brain and the female brain structured differently? Almost definitely not, according to a comprehensive review of brain studies.

In adults, male brains average about 11% larger than female brains, the researchers confirmed, but this corresponds to the larger size of the average male body. In fact, the size difference is even bigger for other organs. For example, men have 23% bigger lungs than women. Bigger bodies need bigger brains to run them. Furthermore, they say, the size difference accounts for structural differences that have been reported, since not all parts of the brain scale up at the same proportion. There's no such thing as a "male brain" or "female brain," because any differences are trivial.

Writing in Nature, study author and neuroscientist Lise Eliot notes that this type of research has a long history of "neurosexism," that is, a bias towards seeking brain differences between the sexes and exaggerating or misinterpreting data to fits the his brain/her brain narrative.

Gladiators' blood was believed to cure epilepsy

The life of a Roman gladiator wasn't easy — or long. Most of these arena fighters didn't live past their mid-20s. And even though combat wasn't always to the death, about one in five to ten matches ended with at least one fatality (per History).

Even after death, a gladiator might find himself exploited. The blood, as well as the liver, of a slain gladiator was believed to be a cure for epilepsy. So much so that according to historian Pliny the Elder, "The blood of gladiators is drunk by epileptics as though it were the draught of life" (via MedPage Today). Gladiatorial games began as funeral rites, and the supposed healing properties of a warrior's blood may also have been a part of that tradition, explained a report published in the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. The idea behind it was the magical thinking that consuming part of a gladiator's body transferred some of the healthful energy that's leaving the dying man's body, according to MedPage Today. Since epilepsy comes and goes, it may have seemed that the gruesome remedy sometimes worked, perpetuating the belief.

After gladiatorial combat itself died out, the blood of executed criminals was used for a similar remedy. It was part of a wider practice called "corpse medicine," the use of human body parts for medical cures. Other examples include everything from ground-up human hair to ointments of human fat, reports Atlas Obsucra.

Freud claimed that fear of castration made men moral

Sigmund Freud is a complex, even controversial figure in the history of psychology (via Scientific American). On the one hand, many of his ideas were groundbreaking, such as the concept of talk therapy, or the idea that the unconscious part of the mind can influence our behavior. But on the other hand, he tended not to subject his theories to any kind of scientific rigor.

Perhaps the most famous of his concepts is the Oedipus Complex, which states that boys view their father as competition for the attention of their mother. One of the effects of this is "castration anxiety," that is, when a boy becomes aware of the physical differences between men and women, he assumes that his mother's penis has been removed. And that his father will do the same to him. This anxiety leads to the development of a sense of morality, what Freud called the super-ego, a kind of inner father that ensures proper behavior (via Verywell Mind).

And the theory gets even less ...let's say, credible ... than that. Writing for Psychology Today, journalist Rebecca Coffey explained that according to Freud, since only men grow up with this fear, only men develop a moral sense. Women, he concluded, are innately amoral and require the guidance of a father or husband. He should have known better: Freud's daughter Anna, who was his closest intellectual companion and an influential psychoanalyst herself, was a lesbian who stayed in a happy monogamous relationship for 54 years.

Does shaving your body hair causes it to grow back thicker?

Everyone's heard this one at some point in their lives. And, really, it's a belief that could apply to either any body. But let's look at it through the male lens. One survey found that although 55% of men said they felt ashamed of their body hair, 56% agreed that men should only shave their face, and 62% said they'd never shaved their back (via New York Post).

So for any dude who'd like to manscape but is worried that their sheared pelt will grow back with a vengeance: Hair does not grow back faster, thicker, or darker after it's shaved. According to the British Medical Journal, research studies have been disproving this claim since the 1920s. Hair just doesn't work that way. When it's cut or shaved, it's the dead portion of the hair shaft that gets removed, while the living follicle remains below the skin, unaffected. As for that buddy who swears it happened to him, it's probably because new hair can look darker as it hasn't yet been exposed to the elements. And stubble that's left behind can seem coarser because the fine tips of the hair have been removed.

Until relatively recently, crying was considered masculine

When a man cries, it's an unusual enough occurrence that people take note. But the idea that men should hold back the waterworks except in the most extreme situations is a modern concept, reported the HuffPost. In previous centuries men cried to express all sorts of emotions, including sincerity and pleasure, according to historian Tom Lutz. In his book "Crying: The Natural History of Tears," Lutz writes that epic sagas from the ancient Greeks through the middle ages are full of freely weeping heroes (via The New York Times).

It could be that this belief is slowly swinging back the other way, though. A 2016 survey of 2,000 men in the UK found that on average, men said they'd cried in front of others 14 times in their adult lives. But they estimated that their fathers cried in front of others an average of five times (via Daily Mail).

By the way, guys, if you're going to cry, you might be better off doing it in front of women. One study found that women were more likely to help a man if he was crying, but a crying man was less likely to be helped by another man.