Everything You Need To Know About Your Liver

Quick pop quiz: List three facts about the human liver. We'll wait.

Okay, so you muttered something about alcohol being bad for it, and you're pretty sure it's somewhere in the neighborhood of the stomach. Sheesh, you fail. And that's a shame, because not only is the liver an important organ, it's the biggest one in your body. In fact, there was a time when the liver was considered by the public to be THE most important bodily organ, and was as talked-about as the brain and the heart (via the Proceedings of the 16th Annual History of Medicine Days, University of Calgary). Even though its popularity has waned, the liver's got a lot going for it, with responsibility for literally hundreds of critical functions, and a remarkable capacity for growth that no other organ can match. The liver is so essential and fascinating that to be ignorant of its properties takes a lot of gall. And you can thank your liver for that, too, because that's where gall comes from (via Britannica).

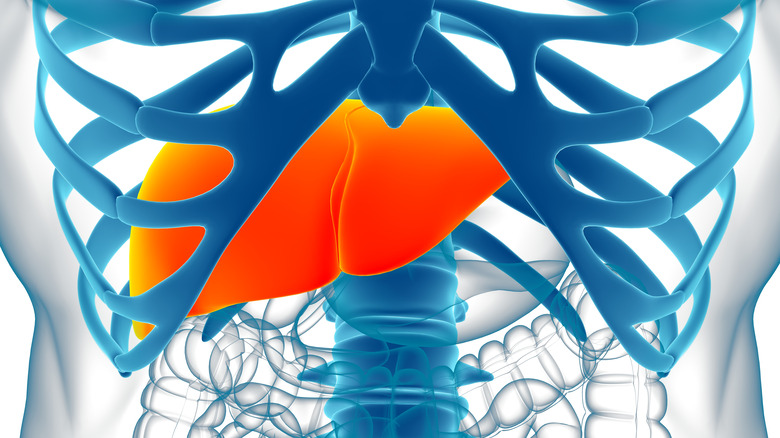

Your liver is kind of a big deal

First things first — some introductions are in order. Say hello to your liver, the wedge-shaped organ that's located under your diaphragm, mostly on the right side (via the Fatty Liver Foundation). It's kind of hard to miss; statistically speaking, the liver is the largest and heaviest internal organ in your body, and the second largest overall after your skin. The liver weighs about three pounds in adults, it's made up of about 300 billion cells ... and during pregnancy it gets even bigger and heavier, to accommodate the extra work it has to do.

Unlike any other organ in your body, the liver receives blood from two sources: an artery that brings blood directly from the heart, and a vein that brings blood from the intestines. The liver's many functions (and don't worry, we'll get into them) require access to the body's blood supply, and at any given moment about 13% of your blood is located in your liver.

So what does my liver do exactly?

Oh, naive reader, what doesn't your liver do? The liver is one overbooked organ, with than 500 different functions that we know of (via Johns Hopkins Medicine). Many of them have to do with regulating the chemistry of your blood. For example, the liver creates blood proteins and cholesterol, and regulates amino acid levels in the blood. It clears the blood of toxins, breaks down harmful substances so they can be excreted from the body, and removes bacteria from the bloodstream. It also produces components that are needed by the immune system.

But that's not all! Not by a long shot. The liver is a key player in the metabolism of the whole body, because it stores and releases the glucose that our cells use for energy (via the Fatty Liver Foundation). It also regulates blood clotting. It stores iron. And it produces bile, a substance that helps your body digest fat. It produces hormones and regulates the levels of other hormones, removing them from the blood when they're not needed. It also breaks down old red blood cells (the failure of this process is what causes jaundice, the yellowing of the skin and eyes that's a classic symptom of liver problems).

The liver was once considered the seat of the soul

Because of its size and the amount of blood it holds, many ancient civilizations considered the liver one of the body's top three most important organs, along with the heart and the brain (via the Proceedings of the 16th Annual History of Medicine Days, University of Calgary). Various cultures around the world believed the liver was the location of the soul and, because it was thought to create blood, the source of life. (We now know that blood cells are made inside our bone marrow ... you knew that, right? Right? Cue Anakin/Padmé meme). Ancient Greeks used "liver" poetically the way we use "heart." Imagine Hank Williams singing "Your Cheatin' Liver," or giving out liver-shaped cards for Valentine's Day.

The liver maintained its rep as the body's most important organ for a long time, thanks to the writings of Galen, a 1st-century Greek physician whose influence lasted through the 17th century (via Britannica). He was a proponent of the four humors theory, which held that human health depended on a balance of four bodily fluids, three of which were created by the liver. It would take closer study by 17th-century anatomists to cast doubt on these ideas and prompt a dethroning of the liver as king of the abdomen. Ranking bodily organs according to importance is misguided anyway, since we need all of them to live (except maybe you, spleen, so watch yourself, via Cleveland Clinic).

The liver is the only organ that can regrow itself

Your liver has many unique properties, but its most amazing trait may be that, unlike any other organ in your body, the liver can regenerate if it's damaged. In fact, as long as 30% of the organ is intact, the liver can usually grow back to full size. It's a phenomenon hinted at in the Greek myth of Prometheus, whose liver was eaten by an eagle every day and grew back overnight. The regeneration may have prolonged his torment, but for someone with advanced liver disease it can be a life-saver: Damaged liver tissue can be removed surgically, allowing healthy tissue to regrow in its place. In a study investigating why this procedure sometimes doesn't work, researchers found that the regeneration process seems to be triggered by a blood protein called fibrinogen, which is involved in clotting (via Thrombosis and Hemostasis) .

The liver's regenerative properties also allow for the organ to be transplanted from a living donor to someone whose liver is failing or damaged beyond recovery (via UCSF School of Medicine). In such cases, a segment of the healthy liver is transplanted from donor to recipient, and the tissue in both parties will grow back to provide normal liver function. The surgery is complicated and challenging, though, and risky for both people. So most transplanted livers are taken from recently deceased organ donors.

If you're a heavy drinker, you probably have liver disease

Starting to appreciate how hard your liver works? Okay, why not do your new best friend a big favor...quit drinking! Alcohol is your liver's kryptonite. The liver has to detox all the alcohol you drink. But breaking those toxic alcohol molecules down releases substances that can harm your liver cells (via Yale Medicine). The process also produces lipids (fats), which can build up and damage the liver. And the alcohol itself can cause inflammation and/or scarring of the liver tissue.

The more alcohol you chug, the bigger your risk. It works a little differently for each person, but as a rule of thumb, the risk goes up if you drink an average of more than one (for women) or two (for men) drinks per day (one drink meaning a 12-oz beer, 5 oz of wine, or a drink with 1.5 oz of liquor). Binge drinking, defined as having 4 (for women) or five (for men) drinks in 2-3 hours, raises the risk. About 90% of people who regularly consume high amounts of alcohol have fatty liver disease, which means damaging levels of fats have build up in their liver. At this stage, there usually aren't any symptoms. Left unchecked, the condition can lead to hepatitis, meaning the liver is inflamed and cell damage is occurring. In the early stages, this can be reversed by abstaining from alcohol. Otherwise, the liver can suffer cirrhosis, which is permanent damage.

When cancer spreads, it usually spreads to the liver

When cancer spreads from its site of origin to another part of the body, it most commonly spreads to the liver. In fact, cancer of the liver is more likely to be secondary — that is, originated from elsewhere — than to have started in the liver itself, according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Scientists have noticed since the 19th century that cancer doesn't spread randomly, and have described this with the so-called "seed and soil" hypothesis (via Nature). The idea is that tumor cells survive best in certain microenvironments, the way seeds grow in certain types of soil.

A recent study investigated why the liver seems to be a preferred soil for cancer cells (via Penn Medicine News). It turns out that the cells of the liver can activate a certain protein, which in turn triggers the activation of other proteins that remodel the liver and make tumor growth more likely. The good news in this is that scientists know the chemical signal that starts this process, and may be able to develop a therapy to shut it down and prevent cancer from spreading to the liver, a major cause of cancer-related death.

Coffee or tea might be good for your liver

Almost a quarter of adults have a condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to the National Institutes of Health (via the National Institutes of Health). It's a condition in which excess fat builds up in the liver, not caused by heavy alcohol use. In 1.5-6.5% of adults, the condition produces inflammation and damage to the liver, and can lead to even worse problems like cirrhosis. Diet and genetics seem to influence who develops NAFLD — it's more common among people who are obese or have type 2 diabetes — but it's not clear why some people develop a more harmful version.

Eating a healthy diet and watching your weight may lower your chances of developing NAFLD, and you might add some coffee or tea to the menu. A study released in 2021 analyzed published research and found that people who drank coffee regularly had a 35% decreased risk of liver fibrosis, the main cause of liver problems in people who have NAFLD (via Nutrients). It could be that antioxidants and other natural chemicals in coffee have a protective effect, though the data isn't sufficient to show how much coffee's required to confer a benefit, or what kind of coffee works best. A prior study also found that drinking herbal tea daily was protective, but again, more research is needed before any recommendations can be made (via Journal of Hepatology).

Liver disease is costly

Not to rank serious illnesses as if they were hot celebrities, but it's safe to say that liver disease doesn't get as much attention as, say, cardiovascular disease. One way to put this in perspective is to look at the economic burden.

Researchers used medical records to investigate costs associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among 4,569 patients over ten years (via Intermountain Healthcare). NAFLD is a condition in which lipids build up and damage the liver, and it's estimated to affect one out of four adults. Assessing the costs of the disease, including hospitalization, ER visits, treatments, and deaths, and extrapolating that to a national scale, showed that NAFLD imposes a yearly burden of $32 billion in the US. For comparison, stroke costs about $34 billion annually, which in terms of billions of dollars is essentially the same amount, the researchers note.

And that's just one type of liver disease. Another study examined data on people with hepatitis C, a viral infection that can lead to cancer, liver failure, and death (via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). The analysis found that in its early stages, the disease increased patients' monthly healthcare costs by 32%; in its advanced states, it raised costs by 247%, according to Science Daily. On average, people with the infection spent over $24,000 a year on healthcare; those with end-stage disease spent nearly $60,000 annually. So not only is liver disease expensive, costs go up significantly as the disorder worsens (via the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases).

Exercise is good for the liver

You may not think your liver as being important for exercise, but without it, any kind of sustained exercise would be impossible. The liver releases glucose, the fuel that muscles use, upping its glucose output to meet the increased demand during exercise (via Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science). It's like a rechargeable battery, releasing energy when we need it, replenishing its energy stores from the food we eat.

Just as the liver is critical for exercise, exercise is important for the liver. Kind of like muscles that get stronger over time when you work out, the liver seems to adapt to exercise by getting better at its job. Researchers have found that with exercise, the liver becomes more sensitive to the body's glucose needs, and more effective at producing energy. Exercise also appears to reduce the levels of fat stored in the liver, which reduces the risk of liver disease. One study published in Gene Expression in 2018 actually found that regular exercise reversed symptoms of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

How do I know if I have liver disease?

Liver diseases don't always produce noticeable symptoms, especially in the early stages (via Johns Hopkins Medicine). But there are signs of big trouble you should be aware of:

Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, due to a pigment that's usually removed from the body. It's typically the first, and sometimes the only, sign of liver disease.

Cholestasis: The flow of bile, a substance produced by the liver that helps fat digestion, is slowed or stopped. This can cause jaundice, dark urine, pale stool, easy bleeding, itchy skin, and abdominal pain.

Unexplained blood loss: Sometimes liver disease triggers vascular changes that causes blood loss in the stomach and esophagus. This can produce vomiting of blood or blood in the stools, as well as thirst, light-headedness, and anemia.

Impaired cognition: When a damaged liver fails to remove toxins from the blood, they can damage the nervous system, producing confusion, impaired judgment, drowsiness, disorientation, tremors, and changes in mood and personality.

No, you don't have to "detox" your liver

Toxic stuff is, well, toxic. And if your liver has the task of cleaning toxins from your body, aren't you doing yourself a favor by cleaning out your liver?

In fact, it's a myth that you need a regular liver "cleanse" to maintain your health or undo the effects of a food or alcohol binge. There's no proof that products and supplements that say they'll detox your liver live up to their claims, as hepatologist Tinsay Woreta told Johns Hopkins Medicine. Nor is there evidence that they can correct existing liver damage, or help you lose weight. If you want to do right by your liver, there are better ways. Cut down on alcohol use. Stay at a healthy weight by eating a healthy diet and exercising. If you're a heavy drinker, or there's a history of liver disease in your family, talk to your doctor about being screened for liver disease.

Let's talk about hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver, a condition that can have many causes — heavy alcohol use, for example (via the National Institutes of Health). But the most common cause is a viral infection. Viruses that cause it are designated hepatitis A, B, C, and so forth. Hepatitis can be acute (lasting less than six months) or chronic (lasting six months or more). Acute hepatitis usually resolves on its own, but chronic hepatitis can cause serious damage to the liver, and even be fatal.

Here's a guide to the ABCs of viral hepatitis:

Hepatitis A: Highly contagious; the virus spreads through contaminated food or beverages. Symptoms like fatigue, nausea, and stomach pain typically last for two months, but the infection doesn't usually cause long-term illness. A vaccine is available.

Hepatitis B: Spreads through contact with bodily fluids like blood or semen; it can be contracted through sexual contact or shared needle use. It can cause symptoms similar to hepatitis A, but not everyone gets symptoms. People with hepatitis B are at increased risk of developing long-term, life-threatening issues like liver cancer. A vaccine is available.

Hepatitis C: Spreads through the blood; most infections are due to sharing of drug injection equipment. In some people, a chronic infection develops, but symptoms might not be felt until advanced liver disease has set in. Since there's no vaccine, anyone who's at risk should get themselves tested.

Hepatitis D and E: Uncommon in the U.S.; can be a concern while traveling (via the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

"Liver spots" have nothing to do with your liver

"WHAT is the DEAL with liver spots?" said some stand-up comedian somewhere, probably. Well, the deal is that these patches of darker skin are not related to your liver at all (via the Cleveland Clinic). Also known colloquially as age spots (yes, they're more common after age 50, but why be so rude about it?), sun spots or, if you went to med school, "solar lentigines."

Those last two names should clue you in on the true origin of the phenomenon. They're triggered by sunlight, specifically the ultraviolet rays of the sun. The spots tend to occur on exposed areas of the skin, like your arms, hands, and face, and they're more common in people who have fair skin or sunburn easily. What's happening is that sun exposure is triggering your skin to produce more of the protective pigment melanin, which can clump to form the spots. Whatever you call them, they're not dangerous. Your doctor can tell if a dark patch of skin is something more concerning. Otherwise, a dermatologist can advise you on options to lighten or remove them.

Your liver makes a quart of bile per day

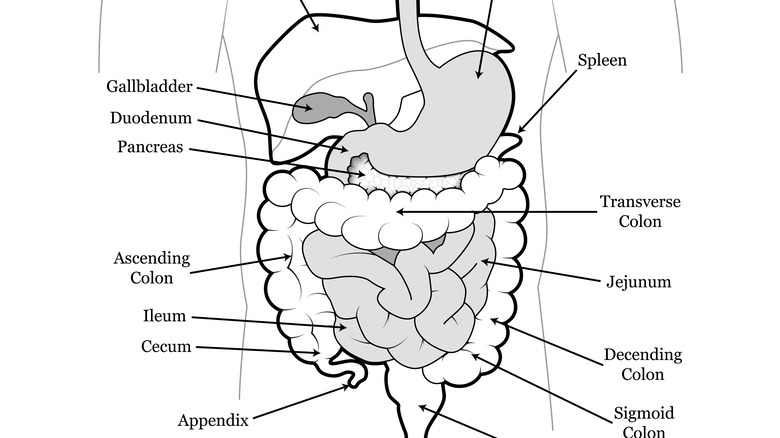

You know how some people always seem to be helping others out, even though they have plenty on their own plate? Your liver is kind of like that. With literally hundreds of tasks on its to-do list, your liver manages to find time to help you digest your food, even though there's a whole digestive system in place to handle that. "Big brother to the stomach," the liver should be called.

The liver's contribution is to create a substance called bile, a greenish-yellow liquid that gets released into the gall bladder, where it's stored and becomes more concentrated (via the National Institutes of Health). Bile that's released into the small intestine helps your body to digest fats, breaking down large droplets into smaller ones so digestive enzymes can do their thing. Most of the active ingredients in bile get reabsorbed and returned to the liver, which can produce a quart of bile per day (via Brittannica).

As helpful as bile is, it has one drawback. Sometimes the waste products that it collects clump together to form gallstones, which can be a painful problem if they end up in the wrong place, though most don't cause any symptoms (via Harvard Health).