Researchers Developed A Virus-Fighting Face Mask. Does It Really Work?

N95 masks are one of the most efficient masks you can wear to protect against airborne viruses. The polypropylene filters in them can filter out at least 95% of the particles in the air, including bacteria and viruses. The filters are made of fibers that attract particles, The Washington Post reports.

A team of researchers at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has worked to improve N95 masks using polycations. These are long-chain molecules with positive charges, and there are a couple of benefits to using them. For one, they are safer than other materials used in N95 masks. but even better, they are more effective at fighting against viruses and bacteria (via MedicalNewsToday).

In a press release, Dr. Helen Zha explained that the masks work through "simple chemistry," as the polycations basically kill bacteria and viruses by "breaking open their outer layer." Another benefit of this technique is that the molecules can be applied to filters on N95 masks, which means that new masks don't have to be manufactured.

The masks kill bacteria and several viruses

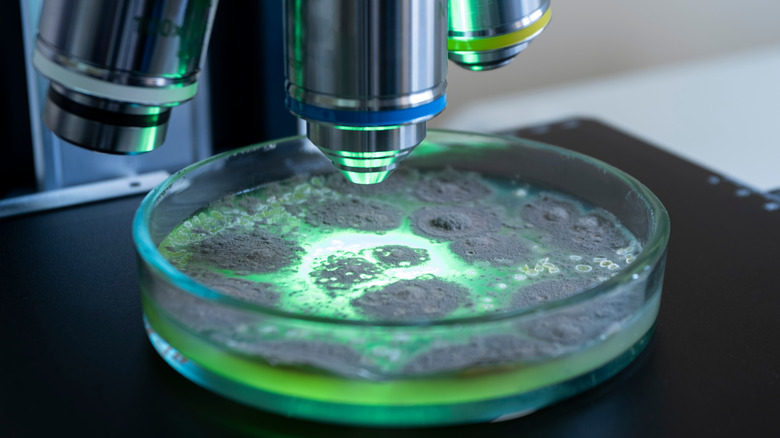

Researchers tested the new masks and found that they destroyed several viruses and bacteria on contact, including Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. In addition, they found that the masks decreased the amount of a mouse coronavirus that resembles COVID-19. They noted that the antiviral capacity of the masks depended on the strain of the virus (via MedicalNewsToday).

While this is good news, scientists acknowledged that the filtration efficiency of the masks decreases after the antimicrobial polymer is applied. However, this problem can be solved by wearing a regular N95 mask under the mask, which has a germ-fighting coating. Masks could be manufactured in the future with the protective layer applied to the outside of the N95 masks to eliminate the need for two masks, per MedicalNewsToday.

This kind of technology is currently only used on masks. However, Shekhar Garde, dean of the School of Engineering at Rensselaer, said in the release that it could be useful in other contexts to help control the spread of viruses and bacteria.