Body Parts You Probably Didn't Realize You Had

The study of the body and all its various parts and structures is referred to as anatomy, according to a 2017 research paper published in the Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. The Greek verb "anatomein" means to "cut open and dissect," as Body World's History of Anatomy explained. That should tell you a lot about how scientists have learned so much about the human body.

Yes, humans have been engaging in anatomical study for thousands upon thousands of years. Consider the fact that we still have ancient mummies to study only because people of the past had learned that preserving a dead body for eternity required removing the inner parts. Still, it wasn't until around the 3rd century B.C.E that human dissection became a bona fide science, as the History of Anatomy explained, paving the way for all we now know, and that includes all these body parts you probably didn't realize you had.

Ever notice your third eyelid? It's called the plica semilunaris

You know how the inner corner of your eye is lined by a small, triangularly shaped pink membrane? That's the plica semilunaris. While it's not much of an eyelid, it does cover a small portion of the eyeball. Scientists think it's what's left of an actual functioning third eyelid still found in other animals — an eyelid known as the "nictitating membrane," according to Science Oxford.

The nictitating membrane was first identified in birds in the late 1800s, according to the authors of a 2017 case study published in the Indian Journal of Opthamology, and was described as a membrane that moves horizontally across the eye, from inner to outer corner.

You might see the nictitating membrane on your dog while he's sleeping with his eyes partially open, according to Animal Planet. Thin and translucent, it closes to help keep the eye moist and protected while still allowing for visibility. The nictitating membrane has evolved out of humans, although the case study referred to above involved a nine-year old girl who was found to have been born with one.

The lacrimal punctum is the hole from which your tears drain

Did you know your eyes are connected to your nose through something called the nasolacrimal system? According to MedScape, the nasolacrimal system consists of a series of tiny tubes and holes. One of those holes is known as the "lacrimal punctum." This tiny hole is located in the lower eyelid — and it's through this hole that clear, salty liquid known as tears drains for the purpose of lubricating the eyeball and flushing out foreign invaders, according to Healthline.

When you cry or otherwise produce excess tears, the liquid drains not only through each eye's lacrimal puncta, but also into the nasal cavity, a report in Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System (Third Edition) explained. That's why when you cry, your nose can feel stuffy. It's also why when you have an upper respiratory infection, your eyes may look glassy and feel irritated.

Although it may seem paradoxical, chronically dry eyes may be caused by excessive draining of tears through the lacrimal puncta and can be treated by inserting a tiny device (known as a "punctal plug") that blocks such drainage, according to the American Academy of Opthalmology.

Deep inside your nose is your vomeronasal organ

One of the reasons you may not be aware of the vomeronasal organ is that it is considered "vestigial," which means it used to serve a function that was necessary for human survival but now is considered useless. As a 2018 research paper published in the journal Cureus explained, the vomeronasal organ is located in your nose's septum, which is the tissue that separates the left from the right nostril. This organ is tiny, sac-like, and contains a duct by which the organ is supplied with blood and lymphatic fluid.

The vomeronasal organ, which is present in other animals besides humans, contains "specialized olfactory sensory cells" (clinically known as "esthesiocytes") that help those other animals detect subtle scents such as pheromones, according to Danish surgeon Ludwig Jacobson, who studied the organ so extensively during the early 19th century that some refer to it as the "Jacobson Organ."

A 2014 study published in The Anatomical Record suggests that this organ's purpose in modern-day humans may be limited to the embryonic stage, with no actual purpose once a human is born.

You may have a pretty useless muscle in your forearm

The palmaris longus muscle is a thin, ropey, tendon-like protrusion that runs vertically through the forearm. One reason you may not know about it is that you may not even have it, according to Physiopedia, which pointed out it may be lacking in one or both forearms in more than 30 percent of the world's population. Moreover, it's not just a matter of whether or not one has it. There is a "high degree of anatomical variations" even when it is present, Physiopedia explained.

Interestingly, the palmaris longus muscle is frequently harvested for reconstructive plastic surgery procedures, according to the authors of a 2005 study published in the British Journal of Hand Surgery. The study also demonstrated that the presence or absence of this muscle has no impact on grip strength — or even pinch strength, in case you were wondering. As such, it's considered a body part humans don't need anymore.

You've probably never heard of this organ

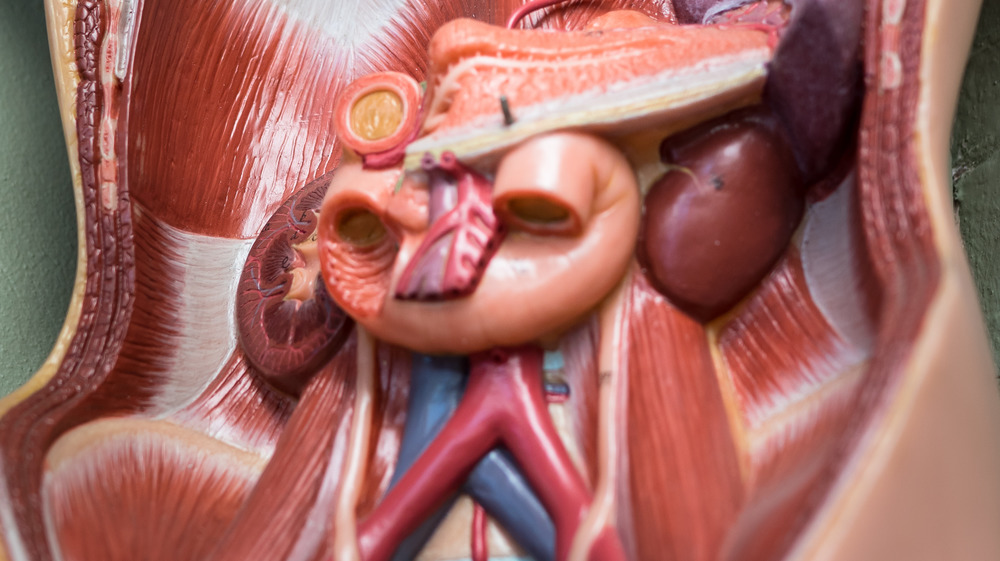

There's a good reason you probably don't know you have a "mesentery," which refers to a folded piece of abdominal membrane that connects your intestines to your abdominal wall — you know, so they won't slosh around in your abdominal cavity (via Mayo Clinic). It actually wasn't until 2016 that scientists could agree that the mesentery was a single, contiguous organ, according to CNN Health. That was when a research paper on the topic was published in The Lancet.

Prior to this research, scientists and other students of anatomy went back and forth as to what exactly it was that held the digestive organs in place. Although Leonardo da Vinci drew the mesentery as a single organ, the prevailing view — as expressed by the first edition of Gray's Anatomy — was that multiple mesenteries were doing the job (via CNN Health).

Scientists still debate whether or not the mesentery should be classified as an organ, but Douglas Adler, a professor in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the University of Utah School of Medicine, told Health Feed Blog, "There will always be talk between the 'lumpers' and the 'splitters.' But the debate doesn't affect its role in your body or how it is treated by doctors."

The lingual frenulum keeps your tongue from wagging

The lingual frenulum is an often overlooked fold of mucous membrane (via Healthline). In the case of the mesentery, that mucous membrane keeps your digestive organs from sloshing around in your abdominal cavity. In the case of the lingual frenulum, the mucous membrane is there to keep your tongue from flapping about, which is to say that it connects the bottom of your tongue to the soft tissues that line the floor of your mouth.

Although the lingual frenulum doesn't get much media attention, it's actually super important for your health and well-being. Any issues affecting the lingual frenulum, whether as minor as a canker sore or as major as being born tongue-tied (clinically known as ankyloglossia), will impact one's ability to use the mouth, including chewing, swallowing, and speaking, as a 2019 case study published in the Journal of Medical Case Reports explained. On rare occasion, a person may be born without a lingual frenulum, but never without a comorbidity such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder.

You've heard of your ACL, but what about your ALL?

You know that ligament in your knee called the "anterolateral ligament"? Yeah, neither do most people. But here's the deal: If you've ever injured your ACL (the anterior cruciate ligament in your knee), you might have dealt with the phenomenon of "pivot shift," which is a sudden giving way of the knee (ouch). According to a 2013 research paper published in the Journal of Anatomy, pivot shift may be the result of an injury to a ligament you may not have even known you had: the anterolateral ligament (ALL).

Considering knee injuries are nothing new, how is it that no one knew about the ALL until 2013? Dr. Steven Claes, a Belgian orthopedic surgeon and lead author of the 2013 study, explained to LiveScience that it's not quite accurate to say that no one "knew" about the ligament prior to the 2010s. Rather, scientists have known there was something there connecting the heads of the leg bones that meet at the knee, going back at least as far as 1879, when a French surgeon wrote about it. However, until fairly recently, no one had been able to isolate the anterolateral ligament in a human body dissection (via LiveScience).

Your philtrum can be found in the space between your nose and your upper lip

Whether you realize it or not, the little vertical groove that runs from your upper lip to the bottom of your nose is an actual body part with its own name. According to Medline Plus, it's called the philtrum. And much like male nipples, it isn't really useful.

However, it does play a role in fetal development. "It is the place where the puzzle that is the human face finally all comes together," Dr. Michael Mosely explained in a BBC One video. The philtrum should be done forming by the end of the third month of human gestation. When the philtrum is improperly formed or fails to form at all, the result is a cleft lip, according to a 2014 research paper published in the Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. However, this is a condition that can be repaired through plastic surgery, albeit a challenging and complicated one.

The arrector pili gives you goosebumps

Humans get "goosebumps" on their skin (clinically known as pilorectio") when they're cold, according to Healthline. The arrector pili also go to work when we're feeling emotionally or sexually aroused, a 2017 study published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology found. Although the development of goosebumps might seem like a small reaction as compared with, say, the digestion of food by your intestines, the fact is that it's the end result of a complicated process involving muscles known as the arrector pili, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Every hair on your body comes out of a hair follicle, and attached to each hair follicle — between the follicle base and the surface of your skin — is an arrector pili muscle. When your skin senses cold temperatures, the arrector pili muscles contract, causing the corresponding hairs to stand straight up. So straight do they stand that each one creates a tiny bump of skin, reflecting that the arrector pili muscle has created enough tension to visibly pull on the skin.

You might not have heard of the cervical rib, especially if you don't have one

Few people have what is known as a "cervical rib," according to a 2020 report in StatPearls. As it happens, cervical ribs occur in up to 1 percent of the population. So what exactly is a cervical rib, and how do you know if you have one?

According to the National Health Service of the U.K., a cervical rib is a an extra rib growing from the base of the neck just above the collarbone. Cervical ribs, which are sometimes known as "neck ribs," form congenitally and can be on one or both sides of the body. Most people who have cervical ribs don't even realize it, according to the authors of the 2020 report.

However, on occasion, a cervical rib can compress nerves or blood vessels, causing pain, tingling, or weakness in the corresponding arm(s), according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. This condition is known as thoracic outlet syndrome, and it can be treated with physical therapy, steroid injections, or surgery to remove the cervical rib.

The hyroid bone is there to keep you breathing

If you're a fan of police procedural television, then you might have heard of the hyoid bone. This free-floating u-shaped bone is, in fact, the only free-floating bone in the entire human body, according to the University of Wisconsin's Waisman Center. It's located in the front of the neck, and it frequently gets name-checked in criminal cases involving death by hanging or strangulation — because the hyoid is found to be fractured in about a third of those cases, a study published in the Journal of Forensic Science revealed.

The purpose of the hyoid is to keep your airways open, as well as to facilitate chewing, swallowing, and speech, a 2020 report in StatPearls explained. You could survive if you were to break it, according to the authors of a 2016 case study regarding a hyoid fracture in a survivor of head and neck trauma, which was published in the Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery. However, hyoid fractures are extremely rare, accounting for only .002 percent of all fractures, so it is unlikely this issue will ever come up.

The auriculares are the muscles that make your ears wiggle

If you can wiggle your ears, you're probably one of only a very few people you know who can. LiveScience estimated that only around 10 to 20 percent of the population are able to control the muscles responsible for ear wiggling, which are known as the auriculares. Those who can wiggle their ears actually have that in common with many non-human mammals, including dogs, cats, and horses. In fact, for most of the animals that can wiggle their ears, ear-moving is critical to picking up sounds (think of the ears of your dog perking up when you speak) and to communicating with others (think of the ears of your dog flattening out when he feels threatened by a bigger dog).

While early humans may have needed to be able to wiggle their ears the way other animals do, modern humans have virtually no need for ear wiggling, except for, of course, entertainment value. As such, ear wiggling is considered a vestigial feature (via LiveScience).

Open wide and say uvula

That tear-drop shaped thing dangling from the back of your throat is an actual body part, complete with a name and a purpose, according to otolaryngologist Zachary Wassmuth, writing for Capital Otolaryngology. The palatine uvula, aka uvula, essentially stands guard between your throat and your nose to keep food that you swallow from finding its way into your nose. It also is one of the touch points (along with your tonsils, the area around them, the roof of your mouth, and the back of your tongue) where the gag reflex can be triggered. In that sense, the uvula helps prevent choking.

You probably don't give much thought to your uvula unless it's sore, which can happen due to strep throat, smoking, or allergies, among other reasons (via Capital Otolaryngology). That is, unless you snore. "When you sleep, your uvula vibrates," according to Dr. Wassmuth. So if you have a long or large uvula, the vibrations may cause a snoring sound. In addition, a large uvula may cause obstructive sleep apnea. In that case, your doctor might consider removing part of your uvula.

Diverticula form in the digestive system as humans age

Diverticula are small, pocket-like bulges that can form in the lining of your colon (i.e., your large intestine), but usually not until age 40 and older, according to the Mayo Clinic. Diverticula are present in about half of all people over the age of 60, but nearly everyone over the age of 80 has them, per the Cleveland Clinic. The presence of diverticula is known medically as diverticulosis.

These intestinal bulges can be anywhere from pea-size to much larger and can form anywhere in your colon. However, they are found most often in the portion that is known as the sigmoid colon, the end of the colon that attaches to the rectum (via Cleveland Clinic). It is unlikely that you would be aware of any diverticula you may have already developed — unless they become inflamed or infected, which is known as diverticulitis.

Symptoms of diverticulitis include pain and sensitivity in the lower left side of the abdomen, fever, chills, cramping, and rectal bleeding, according to Medline Plus. More serious cases of diverticulitis may require a hospital stay for treatment that may include surgery.