A 17-Year-Old Scientist Creates Infection-Detecting Stitches

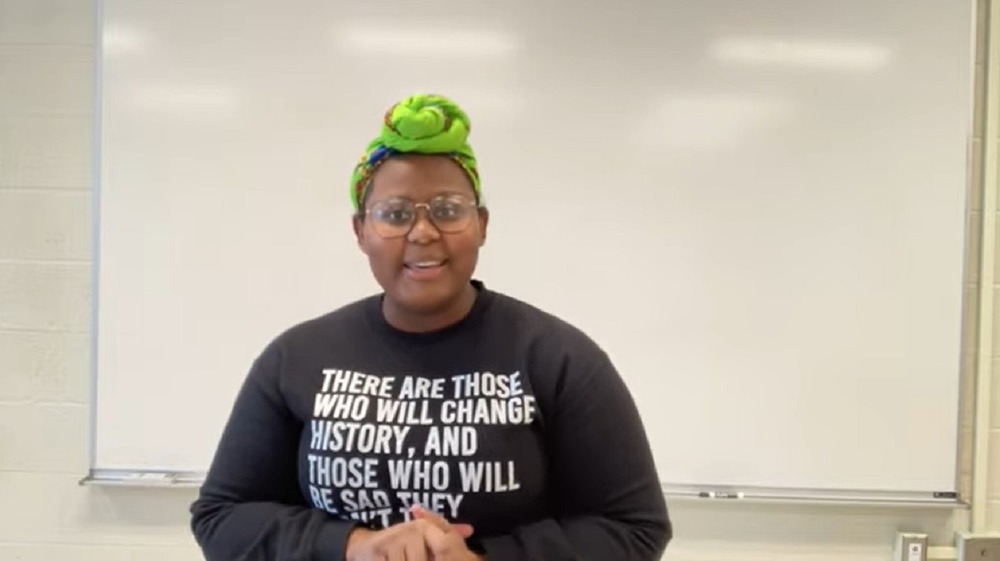

COVID-19 and a renewed spotlight on equality have thrown much of the world into disarray over the last year and a half. And many people are just trying to get through. But one high school student saw the challenges around her and found a decisive way to affect change. Her name is Dasia Taylor, and at 17, she is developing infection-detecting sutures that address a very pressing real-world need.

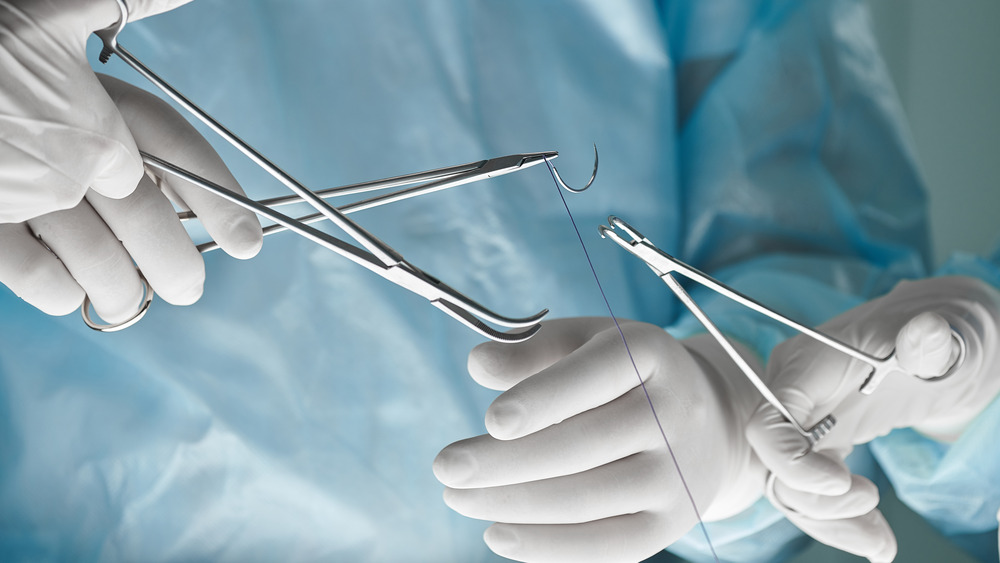

The project began when Taylor read about a form of "smart stitches" that detect infection and send an alert to both the patient and the doctor's devices. While these sutures are great for places with regular Wi-Fi and where people can afford sutures with small battery packs they are less suited for developing and recovering nations (via the National Academy of Engineering).

It is in these nations where infection-detecting stitches are most needed. The World Health Organization reports that around 11 percent of surgical sites become infected in developing and recovering nations. Americans, by contrast, only have a 2 to 4 percent rate of surgical infection (via JAMA Surgery). Taylor was well aware of inequality's impact on these numbers. At 16 she was featured in a Des Moines Register article addressing inequality in her own school district and she is a regular advocate for equality measures both in her community and beyond.

Working around the pandemic

With her advocacy experience and the information on "smart sutures" in mind, Taylor knew what direction she wanted to go when her chemistry teacher announced an upcoming state-wide science fair. Before COVID-19 sent the country into lockdown, Taylor spent Friday afternoons working in her school's chemistry lab, according to a Smithsonian Magazine article detailing her work. Taylor's teacher, Carolyn Walling, helped guide Taylor in her work and provided a critical eye to her student's process.

When the country went into lockdown, Taylor changed her approach. She began spending four to five hours in the lab on asynchronous days, or days when other students would not be in the room. And her dedication paid off. She won awards not only at the state science fair but at multiple regional competitions as well, all the while still working on the sutures. She has now placed in the top 40 of the Regeneron Science Fair, which is run by the Society for Science.

"To get to the Top 40, this is like post-doctoral work that these kids are doing," Maya Ajmera, the CEO of the Society for Science, told Smithsonian Magazine. And she's not exaggerating.

What Taylor plans to do next

In order to make her sutures work, Taylor first had to find a suitable dye. She wanted to work with natural sources and so she started with fruit and vegetable dyes, ultimately choosing beets.

"I found that beets changed color at the perfect pH point," Taylor explained to Smithsonian Magazine. Healthy human skin has a pH of five, making it fairly acidic, according to the International Journal of Cosmetic Science. The lower pH something has, the more acidic it is. And infected skin, by contrast, has a pH of about nine. Taylor found that beet juice, when exposed to skin with a pH of nine, goes from bright red to dark purple.

"That's perfect for an infected wound," said Taylor. "And so, I was like, 'Oh, okay. So beets is where it's at.'"

Taylor also tried several different types of suture material. She eventually found that a cotton-polyester blend held the dye best. Unfortunately, cotton also creates a higher risk for bacterial infection, according to Smithsonian Magazine. But Taylor has a solution for that as well. She has contacted Theresa Ho at the University of Iowa for help in determining the antibacterial properties of beet juice, among other approaches.

You can hear about Taylor's experiment in her own words in this YouTube video from the Society for Science. She is a remarkable student with big plans and all the drive necessary to achieve them. After she graduates from her high school in Iowa City she plans to attend Howard University and major in political science as her next step to becoming a lawyer and continuing her work to change the world.