Surprising Things About Women's Bodies People Used To Believe

In the past, the male body was thought of as the "normal" one, the prototype, the ideal, while the female body was considered weak and flawed (via Standford University). This wide gap in how men's bodies and women's bodies were viewed dates back eons (via NBC News). Why such stunningly fanciful, not to mention clearly erroneous, beliefs about the female body? There are many theories, but "the most plausible theory we have: fear of female sex," Rachel Maines, visiting scholar in Cornell University's Department of Science and Technology Studies, told NBC News.

Fear of the female sex no doubt has its roots in women's ability to create and grow an entire human being. If that isn't black magic, what is? Historical figures responsible for these beliefs about the female body — including writers, doctors, philosophers, and scientists — were, of course, male. Now, with women having become writers, doctors, philosophers, and scientists for a long time, myths about female anatomy have died out. Or have they?

The uterus can move about the body

Originating with the great ancient thinkers in Greece, the "wandering womb" was a thing for quite some time. Even Hippocrates, arguably the most prominent figure in the history of medicine, believed that the uterus would free itself and wander around the abdominal cavity. Not take a leisurely stroll, mind you, but move about heedlessly, colliding with various internal organs, such as the spleen and liver.

The result was that the woman with the restless uterus would suffer from various medical problems. Another Greek physician, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, spelled it out: If the womb moved upward in the body, the woman would become weak and sluggish; if the womb moved downward, she would choke, lose her ability to speak, and, most probably, die suddenly and terribly (via Wired).

One cure for the wandering womb, which was also thought to account for women's "irrationality," was to lure it back into place using scents. Pleasant fragrances applied to the vagina would tempt it to return, while putrid smells from above would force it to retreat from the upper body. In fact, Victorian women carried smelling salts, as they were thought to swoon when overcome by emotions, a report in Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health detailed. Another remedy for the wandering womb was to be pregnant constantly, so the uterus wouldn't stray. Or, as doctors recommended, consent to lots of sex.

Virgins could suffer from green sickness

They weren't necessarily envious but virgins who lived in the 16th century could still be green, due to a malady called green sickness, aka the "virgin's disease." It struck mostly chaste young women and caused their usually rosy complexion to become deathly pale. They also became lethargic and weak. It won't shock you to learn that the cause of a virgin's green-sickness was thought to be her uterus (via The Mary Sue).

As it was believed at the time, before a young woman got her period, her humors (blood was considered one of the four humors, or liquids, of the human body) would collect in the uterus, decaying. Luckily, the stricken woman had options to cure her illness. She could choose to drink "steel water," a delicious mix of steel filings and powder boiled in white wine, sometimes topped off with sugar and spices like cloves or nutmeg. Combined with frequent exercise, this potion would unblock the humors coagulating in her uterus. Another cure was to apparently stop being lazy and idle.

The last option was to procure a dose of "male seed." It was believed that, through sex, sperm could "settle" the percolating uterus by allowing the humors to drain. There was even a folk song written about this cure called "A Remedy for the Green Sickness," in which a miserable young woman is happily assisted by the young man next door.

The myth of 'vagina dentata'

Known in Latin as "vagina dentata," this myth has been part of folklore in cultures around the world, from Austria (where Sigmund Freud is credited with coining the phrase in 1900) to India, South Africa to New Zealand, according to Vice. The idea of a vagina lined with teeth can be traced back to Greek mythology.

"If there was ever a male paranoid fantasy, that was it," Rachel Maines of Cornell University told NBC News. Indeed, theorists say the toothed vagina springs from male anxiety about castration, as well as fear of women's "dangerous" and powerful sexuality. Intercourse with a vagina dentata is threatening in that it could very well sever a man's penis. Clearly, those teeth must be removed. Many stories based on this myth conclude with the heroic male breaking off the vagina dentata, allowing him to safely have sex with the woman (per Bustle).

Historically, vagina dentata was used to bolster the myth that women were to be feared, and that a "patriarchal power paradigm," was needed to keep women in control, along with the requisite belief that men were entitled to sex, Bailey Gaylin Moore, author of "Second Molars," told Hello Flo. But these days, could it act as a symbol of empowerment? "I see it as a way for women to reclaim that their vaginas are a powerful, mystical [force] to be reckoned with — unlike the delicate flower analogy we are socialized to buy in to," sex educator Kenna Cook told Hello Flo.

A woman's nose is connected to her genitals

Back in the day (1897, to be precise), even educated doctors got things wrong about women's bodies. One of those physicians, Wilhelm Fliess, a German ear, nose, and throat specialist, wrote about there being was a close connection between a woman's nose and her private parts (via NBC News). So close in fact, that if there were a problem in one, symptoms would also be felt in the other. He penned a treatise in which he detailed the "nasogenital reflex."

He called out one part of the nose, a bony projection known as the nasal inferior turbinate, as being a particular troublemaker. He believed that symptoms such as headaches, general body pains, problems with breathing and menstruation, and mood changes began in the nose. Eventually, neurosis would develop.

Fleiss was the personal physician of Sigmund Freud and together they decided that the neurosis could be treated with cocaine. Ever willing to go the extra mile, Freud tried the treatment and discovered it could possibly work. The duo concluded that a woman's genital problem, and its accompanying mental illness, could be treated via the nose. Thankfully, the nasogenital reflex theory faded as medical knowledge progressed.

The omnipotent 'monthly flux'

It's amazing the variety of bad things it was believed menstrual blood could do. Notably, Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist, considered himself an expert on menstruation as he wrote all about it and summarized the havoc period blood could apparently wreak. "Contact with the monthly flux of women turns new wine sour, makes crops wither, kills grafts, dries seeds in gardens, causes the fruit of trees to fall off, dims the bright surface of mirrors, dulls the edge of steel and the gleam of ivory, kills bees, rusts iron and bronze, and causes a horrible smell to fill the air," he wrote (via Bustle). Dogs who came into contact with the blood (how?) would "become mad" and their bite would turn poisonous. And, just to drive the point home, Pliny claimed that just a single thread from a dress stained by menstrual blood could divide the salt-thickened Dead Sea into two. We get it, Pliny.

Moving along to medieval Europe, it was believed period blood was both a cure and a curse. It was accepted back then that having intercourse with a menstruating woman would cause the penis to deteriorate, and that imbibing period blood would give you leprosy. Meanwhile, Hildegard von Bingen, a Benedictine nun, mystic, and composer, claimed that drinking it was a cure for leprosy.

In 1919, the dangers of period blood were "scientifically" proven by one doctor who claimed it contained a poison called "menotoxin," potent enough to cause illness in the woman herself, as well as her children. Of course, we now know menotoxin isn't real.

Women were actually men who hadn't fully developed

Before the 18th century, women weren't seen as a separate sex, but as a lesser version of men, or men at a "lower stage of development," revealed the Journal of International Women's Studies. The ancient Greeks considered humans the perfect life form, and men "more perfect" than women, based on the belief that all living creatures were on a spectrum. Those with the lowest heat were on one end, and those with the highest heat, i.e., men, were on the other. Women's bodies were "cooler" because they were thought to produce semen that was "thinner and cooler" than men's, according to Galen, a Greek physician, surgeon, and philosopher in the Roman Empire.

Galen also believed that men's and women's genitals were the same except for their configuration and placement. He considered the ovaries and Fallopian tubes to be internal testes and seminal ducts. This view of women as lesser men has been called "phallocentric," as it allowed medical science to use "facts" about women's bodies to justify men's authority and provide reasons why women were abnormal.

The belief in "one sex" continued through the Renaissance. Even though autopsies were performed, experts still thought that the female body was an inverted version of the male. It wasn't until the late 17th century and early 18th century when medical advances and cultural changes occurred that a two-sex model emerged.

The pervasive myth of 'virginity tests'

The idea that a torn hymen indicates a woman is no longer a virgin may have originated as far back as the 16th century, Dr. Dennis Idowu, medical director and co-founder of a women's health urgent care center, told Bustle. Although a 1906 study proved this to be an unreliable test, the myth continued (via The Guardian).

"[The hymen] is a thin mucosal membrane that surrounds or partially covers the vaginal opening," Dr. Mary Jacobson, chief medical director at Alpha Medical, told Bustle. However, not every woman has one. Additionally, it is elastic and can remain intact even after intercourse. It can also sustain damage through non-sexual means, like inserting a tampon and horseback riding. Clearly, the hymen is nowhere near a reliable indicator of virginity.

Yet, these so-called "virginity tests" are not unheard of today. In 2017, a small study found that 16% of OB-GYNs surveyed in the U.S. had been asked to do a virginity check or perform virginity "restoration" (surgery to reconstruct the hymen). About 30% of those doctors did what was requested, according to The Guardian. This myth seems to be a stubborn one, as medicine tends to stick to outdated textbooks and research primarily focused on men.

Women age faster than men

Our modern-day fascination with and attraction to all things youthful is actually quite old. It has its roots in the mid-Victorian age, when the study of aging (gerontology) began (via The Conversation). As the first gerontologist, George Edward Day, made some progressive strides in the study and treatment of older people, but he also managed to have unnerving beliefs about how women age.

Like other Victorian physicians, Day was influenced by classical thinkers such as Hippocrates, who claimed that women aged more quickly than men. There was also the Victorian belief that the female body was physically and emotionally weaker than the male's. Day took these a step further by theorizing that women enter old age before men do (40 versus 48 to 50, respectively) and retain the lead in the aging process. Women, Day said, were five to 10 years older biologically than men the same age.

We no longer believe there's an aging disparity between the sexes. Men and women age at about the same pace. However, the anti-aging treatment market doesn't act like this is the case. The target consumer is clearly female — and, in some cases, women in their 20s who aren't showing signs of aging yet. The message behind the ads is that women need to act quickly to stop aging from progressing. Is the myth that women age faster than men entirely gone? Not according to the $250 billion global anti-aging market, which emphasizes that its products are an emergency treatment for women (via The Conversation).

If a woman went to college, she would wind up infertile and ill

Heading into the Victorian era, there was the belief that women had a pathological biology, with a smaller brain and weaker muscles than men. In addition, the entire female body was under the control of the reproductive organs (via Encyclopedia.com). The uterus and ovaries were directly responsible for any illness that could befall a woman or indirectly responsible through "reflex irritation," which was when the reproductive system caused disorders in other parts of a woman's body. Women were naturally frailer and more sickly than men, and more prone to emotional excess.

In the mid-19th century, women began to challenge traditional gender roles in society and previously accepted economic patterns. Under the threat of women attending universities, doctors — widely portrayed as experts on female physiology — used science as a way to claim women couldn't be college-educated. One eminent physician, Edward H. Clarke, a Harvard professor and author, was a proponent of the belief that the human body has a limited "energy bank," with a constant battle raging among the organs for resources, Encyclopedia.com detailed.

During puberty, learning interfered with the healthy development of a girl's reproductive system, as the brain and uterus fought against each other, Clarke claimed. If that girl went on to college (and survived), she'd be infertile and sickly. Such "scientific" arguments were used to legitimize traditional gender roles and prevent women from getting an education, accessing birth control, or entering "male" professions.

Women suffered from hysteria and needed this particular treatment

Even after the realization that women were a separate sex, the "experts" (still men) weren't very interested in exploring whether or not women could experience sexual pleasure (via Refinery29). Instead, in an odd, round-about way to understanding female sexual pleasure, they invented a mental illness, then a device to cure that illness. Hence, the vibrator was born. Let's go back to the late 19th century to see how this happened.

In the 1800s, people didn't believe women could have sexual pleasure the way men did. If a woman exhibited horrifying symptoms such as persistent arousal, erotic fantasies, or excessive vaginal lubrication — or more "typical" female problems like fainting, sleeplessness, or anxiety — she was diagnosed with hysteria, a basket term for all kinds of vague health problems women were prone to, and needed treatment, according to "The Technology of Orgasm" by scholar Rachel P. Maines. To alleviate the horrors of hysteria in a female patient, a physician would lead her to experience a "paroxysm," now known as an orgasm, by massaging her private parts. Women themselves couldn't do it — too unlady-like — and doctors soon grew weary of having to provide this medical practice to so many patients.

Then in the 1880s, a solution! The vibrator was invented. Still, the diagnosis of hysteria continued. It wasn't until 1952 that the American Psychological Association stopped considering it a disorder (via NPR). And we all know what happened to the vibrator.

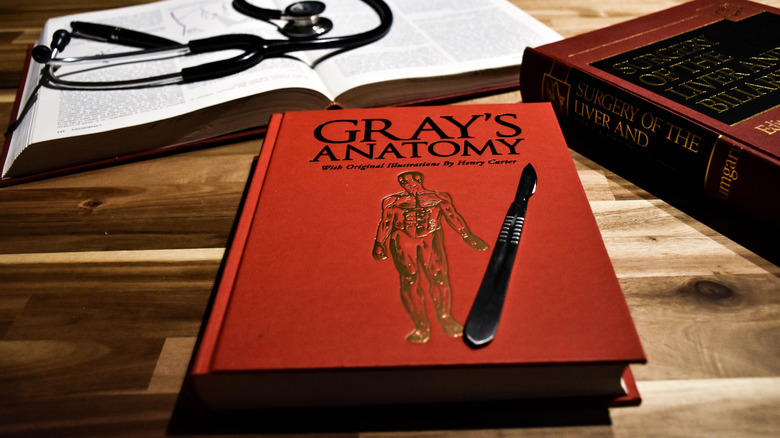

This part of the body vanished from medical textbooks

Back in 1672, a Dutch anatomist produced a depiction of the clitoris, neglecting to include its inner structure, which we now know is shaped like two wishbones and measures up to four inches across (per The Nation). Then, in 1844, a German scientist drew a schematic of the clitoris, including both its internal and external parts. So far, so good.

Then, something odd happened. The entire organ went missing from the 25th edition of "Gray's Anatomy," published in 1947, for reasons unknown. It was only some two decades ago that an accurate depiction of the clitoris, with both its inner and outer workings, was published in 1998. Not only that, but the drawing revealed that the organ has three times the number of nerve endings in the penis. It is (rightfully) included in the 41st edition of "Gray's Anatomy" — that's scientific validation for an organ whose sole function is to provide pleasure to its owner.

Orgasming the right way?

Orgasm-shaming is a thing. You can thank Sigmund Freud for that. The father of psychoanalysis concluded that if a woman had orgasms through clitoral stimulation, she was sexually and psychologically immature. And she likely had a mental illness, like psychosis (via TalkSpace). Could it be that the vaginal orgasm was dubbed "better" than the clitoral orgasm because it involves penetrative sex, which is preferred by men? And could it be that there's really no distinction between the two types of orgasm? Hmm. "Because everyone is so different, setting this norm that vaginal penetration is the main way, or most valid way, to achieve an orgasm is not only destructive to female sexuality but is also majorly patriarchal," Alexis Thomas, a sex educator, told Bustle.

After much-needed research, the current view of female orgasm is that it arises from stimulation of the "clitourethrovaginal complex," which is a series of nerve endings that extends into the body from the outer part of the clitoris, according to TalkSpace. There actually aren't distinct vaginal and clitorial orgasms — different sensations come from stimulation of different parts of the complex. That also means that a "vaginal" orgasm involves the clitoris in some way. "Any vaginal stimulation causes clitoral stimulation," sex researcher Nicole Prause told Bustle. "They are, quite literally, all connected."

Were women really institutionalized for reading novels?

Could women have been institutionalized in the 19th century for reading novels and being "lazy"? Between 1863 and 1889, the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum, a mental hospital in West Virginia, kept a logbook of its admissions (via Snopes). A list of reasons for admissions, compiled from this log, was published or referenced in subsequent books and research papers.

One book, published in 2001, included the list to show how easily a husband could have his wife institutionalized toward the end of the 19th century. The author, Maureen Dabbagh, wrote that reasons for admittance to this facility included "laziness, egotism, disappointed love, female disease, mental excitement, cold, snuff, greediness, imaginary female trouble, 'gathering in the head,' exposure and quackery, jealousy, religion, asthma, masturbation, and bad habits" (via Snopes). Novel-reading even made the list.

These weren't symptoms of mental disease, per se, but rather reasons why patients might have gone on to develop illnesses such as dementia, mania, and melancholia — which is what caused their hospital commitment.

Women could transform into werewolves

"She-wolves" aren't just subjects of popular 21st-century songs. Back in 14th-century Europe, a deep-seated fear of witchcraft swept like an undercurrent across the continent. People believed witches partook in devil worship and, at night, engaged in lycanthropy — shifting shape from woman to wolf. Western thinking would have everyone believe that the werewolf community was vast.

It was, according to believers, also criminal behavior. Many thought that these "wolves" mauled and ate children. The torturous act was at least one of the reasons the accused were subject to the infamous European werewolf trials through the 17th century. Some even "confessed" to the crimes and admitted they were actual child-gobbling beasts in the night. This did nothing to quell the panicky fear that overwhelmed the public. Medieval zooarcheologist Aleksander Pluskowski, who penned "Werewolf Histories," wrote, "The idea of being consumed by animals, in this world or the next, remained a popular anxiety throughout the Middle Ages" (via History). The punishments fit the purported crimes, with hundreds sentenced to death by fiery execution.

There's also the lore of the women-turned-wolves who were said to have tortured and maimed the males and even the livestock of the Duchy of Jülich during the 16th century. The tale suggests that some 300 women transformed into werewolves, committing atrocious crimes of cannibalism in the aftermath. However, there's no real evidence that these female wolves ever stood trial for their behaviors, nor is there actually any proof that such women even existed.

Birthmarks and moles were signs of a witchy presence

While beauty marks in the modern world are often linked to supermodel heights of glamour and elegance, that was decidedly not the case during the 17th century. In fact, these "lesions" were considered signs of a woman's witchy ways. Those who bore what were known as "witch's marks" on their skin, whether a birthmark or a mole, were automatically thought to have entered into a pact with the devil himself.

It was fear-mongering of the highest order, which meant the presence of a birthmark or mole on a woman's skin could lead to severe accusations — and, in some cases, even life-threatening consequences. Those who possessed these so-called witchy lesions were often subjected to invasive examinations by witch hunters, who believed that the marks were used to nourish their demonic familiars, or their connections with the devil.

The paranoia led to tragic outcomes for many women. For example, Grace Sherwood was repeatedly accused of being a witch. An investigation of her body bore fruit for the accusers, who found marks on her body and sentenced her to be tossed in a river with a 13-pound Bible around her neck (not to mention her right thumb tied to her big toe on the left side of her body, and vice versa). It was determined that her innocence was proven if she sank. However, Sherwood managed her way out of the binding and swam to her freedom — only to receive an eight-year jail sentence.

Corset wearers were doomed to an early death

Today, many wear corsets in an effort to "train" their waists and create an hourglass silhouette. While some say that wearing these restrictive garments could be unhealthy, there's no risk of actual death. In the 19th century, though, those who worse these Victorian wardrobe staples were thought to be endangering their health. Doctors at the time even issued stark warnings about wearing them, suggesting that corsets could be to blame for everything from liver disease to tuberculosis to heart problems.

In fact, articles published in 1890s-era editions of The Lancet, a medical journal, informed the public that it was very possible that corsets could lead to an early demise (via CNET). An early 20th-century copy of the Yorkshire Evening Post published an article titled "Death from Tight-Lacing: Manchester Girl's Fatal Vanity", in which the corseted "victim" was said to have met her end in the most unseemly of ways. "The liver, intestines, stomach, and other organs were all jumbled up together, and were remarkable for their smallness," it read.

Despite these beliefs, anthropologist Rebecca Gibson discovered something surprising during her research on the effects of corsets on the skeleton. Her findings revealed that corset-wearers actually met their life expectancies, and in some cases even exceeded them. She explains to Forbes that the information decries [t]he very popular notion that corseting was inherently overly harmful, as well as the longstanding medical belief that corseting was responsible for early death."

Ladies could develop bicycle face from riding a bike

Most wouldn't typically consider a leisurely bicycle ride to be an extreme sport. In the 19th century, though, the activity was said to pose a significant threat to women. It wasn't because of the risk of an accident, but due to the belief that women would develop a condition dubbed "bicycle face." This completely faux malady warned of the purported dangers women faced whenever they rode a bike. "Symptoms" were thought to include bulging eyes, jutting chins, and wan faces. Doctors railed against the activity, stating the effects were permanent and life-altering.

The hysteria was manufactured largely because the two-wheeled vehicles gave women a new lease on life, allowing them the freedom to get around on their own — without any need for the male persuasion. It marked a dramatic cultural shift for women, too. Frances Willard, a suffragist who founded the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, was so inspired by the progress brought about by the bicycle that she wrote a book about it. She also criticized popular women's garb of the day, stating that the snug corsets and weighted skirts were impractical for riding. The outrage eventually inspired a new breed of women's fashion, including lighter weight clothes and even pants.

"Bicycle face," then, was really just a myth perpetuated by those who were threatened by the newfound freedom that women enjoyed. Instead of suppressing their independence, though, the "diagnosis" really only revealed the anxieties ingrained in society at the time.