The Real Reason So Many Epidemics Start In Asia And Africa

COVID-19 continues to circle the globe, hospitalizing many and ending the lives of others. It is a pandemic like most alive today have never seen. As terrible as it is, however, it is not entirely unfamiliar. As is the case with many recent strains, COVID-19 originated on the Asian continent.

It has led many to blame the Chinese people for the creation and spread of the disease. Stereotypes and assumptions have led hate crimes to a 12-year high in the United States as Asian Americans, as well as Black Americans, are targeted (FBI via Reuters). But people do not trigger the diseases that come out of Asia or Africa, at least not directly.

COVID-19 and similar diseases are known as zoonotics or zoonoses, according to the CDC. These are viruses and diseases that start in animal populations before making the jump to humans. They can start in both wild and domestic populations, but their jump to humans requires the same thing: extremely close and regular contact between humans and infected animals. In both Asia and Africa, changes are taking place that create a perfect firestorm for zoonoses, as a Penn State virologist explained in 2020.

Habitats and health

Dr. Suresh Kuchipudi spoke with The Conversation in March of 2020, shortly after much of the world went on lockdown against COVID-19. Kuchipudi is the associate director of the Animal Diagnostic Lab at Penn State, specializing in zoonoses. Holding several accreditations including a B.V.Sc., M.V.Sc., Ph.D., and a DipACVM among others, understanding these types of infections is at the core of what he does.

In his interview with The Conversation, Dr. Kuchipudi explained that many parts of Asia are undergoing rapid urbanization, which in turn leads to widespread deforestation and the displacement of countless wild animals. He cites a 2015 World Bank report stating that in the first decade of the 21st century, nearly 200 million people relocated to urban centers throughout Asia. Kuchipudi puts this into perspective by stating that 200 million people would create the world's eighth largest country if they all relocated to the same place.

When this many people migrate to urban areas, the need for housing, shops, and employment skyrockets. This in turn drives deforestation through clear cutting to make room for new construction. As humans stretch further and further into formerly wild land, the animals that once lived there come into contact with the new inhabitants, human and animal alike. The result is the spread of zoonoses.

Domestic animals carry risk too

Of course new construction happens all over the world. But the rate of new construction throughout Asia and a variety of Pacific countries is the specific situation that can trigger zoonoses. The same can be said of Africa, as explained by a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America. Rapid urbanization and relocation of human populations cuts down the natural habitats of wild animals, specifically rodents. These animals remain in the same place where they are hunted by — and fight with — domestic animals, while leaving disease vectors on surfaces that humans come into contact with.

As the CDC explains, these are both paths by which zoonoses can jump from animals to humans. Humans come into contact with the infected surfaces and become infected themselves. Or the infection passes to their pets before making the jump to the human population. This is one reason Dr. Neilanjan Nandi told The New York Times in 2016 that people should avoid letting their pets lick them.

It's a suggestion backed up by a 2015 study published in the Journal of Medicine and Life. The study focused on the transference of disease from dogs to humans. In it, man's best friend is described as a "major reservoir for zoonotic infections". Far from trying to malign dogs, however, the report was written as an attempt to educate the public and reduce zoonoses transmission.

Transmission pathways

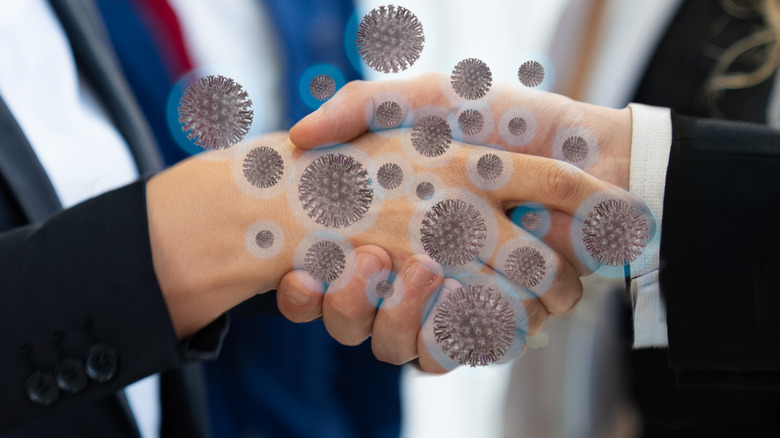

Pets and infected surfaces are not the only ways that zoonoses can spread, however. The CDC refers to these as direct and indirect contact, and adds that direct contact can also include being bitten or scratched by any infected animal, whether wild or domestic. These are the first two routes listed, but the CDC provides an additional three ways that zoonotic infections can spread.

Of these three, the one most people are likely to be familiar with is vector-borne transmission. This form of disease transmission takes place when a human is bit by a tick, mosquito, or other disease-carrying insect. Food-borne is another transmission pathway and one Dr. Kuchipudi touches on, though in a different manner than the CDC. In his interview with The Conversation, Dr. Kuchipudi explains that eating bushmeat can also transmit zoonoses. The CDC brings the risk closer to home by highlighting the transmission risk posed by unpasteurized milk and its products, undercooked meat and eggs, and produce that may have come in contact with contaminated animals or their feces.

The final transmission risk comes through contaminated water. These infections are termed as waterborne and typically occur when drinking water becomes infected through the feces of infected animals. This sort of contamination is more common in areas where drinking water is limited or protection regulations are not yet in place: a situation Dr. Kuchipudi discusses when explaining the zoonotic effects urbanization has on those still in rural areas.

Transmission in rural areas

Speaking with The Conversation, Dr. Kuchipudi further breaks down the issues surrounding rapid urbanization. He focuses specifically on those who remain in rural areas, where there may be less access to clean drinking water and fewer protective restrictions in place. Like deforestation, this can occur anywhere in the world. But Dr. Kuchipudi explains that it is especially dangerous in tropical areas, like many parts of Asia and Africa, that are rich in host biodiversity. As explained in the journal Nature, this means that these areas have a higher number of animals that can transmit zoonotic diseases.

This issue combines with the fact that many people who do not live in urban areas rely on subsistence farming. Such farms usually have limited resources and may have limited space. Their livestock ends up in close proximity, regardless of species, with the human inhabitants often living very close to the animals' housing. The livestock may also come into contact with wild creatures, further increasing the risk of passing along an infection.

Reducing transmission risk

These facts may paint a bleak picture. For many it may seem as though transmission is unavoidable. But as the World Health Organization assures us, this is not the case. The WHO states that there are over 200 currently-identified zoonotic diseases. Many of them are treatable and some, like rabies, are completely preventable with vaccination. Certain behaviors, such as fully cooking meat and eggs or washing all produce before eating it, can also reduce the risk of disease transmission.

The World Health Organization also suggests the widespread implementation of health and safety standards in agriculture. It is a large project and one the WHO is working on with the help of multiple agencies. Due to the scope of the work, however, it will likely take some time to fully implement the changes. Until then, each person can reduce their own infection risk by thoroughly washing their hands after contact with animals, and by reducing their risks of food and waterborne transmission (via the CDC).