The Shingles Vaccine: A Comprehensive Guide

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that one in three people will get shingles in their lifetime, and estimates there are about 1 million cases in the United States every year. Herpes zoster is the clinical name for this viral infection (per Cleveland Clinic). It is brought about by the varicella-zoster virus, which is also responsible for chickenpox.

Shingles typically presents as a painful red skin rash with fluid-filled blisters on one side of your waist, stomach, chest, face, or neck. The telltale sign of the shingles rash is that it appears as a patch or band on one side of the body. The feeling has been described as tingling pins and needles to burning, shooting pain. It can take almost two weeks for the blisters to dry out, and another two to three weeks for the skin to clear up. What's more, complications like nerve damage can lead to debilitating pain lasting for months, even years afterward (per the CDC).

If you were born before 1980, chances are you've had chickenpox, which puts you at risk for developing shingles. When you recover from chickenpox, the varicella-zoster virus becomes inactive, but remains in your system. It resides in the dorsal root ganglia, a part of your spinal nerve. If reactivated, the virus spreads along the nerve fibers, causing skin pain, rash, and blistering. Researchers aren't sure how the virus is reactivated, but they believe it may be from stress, trauma, chronic illness, or a weakened immune system (per Cleveland Clinic).

What are the symptoms of shingles?

Early symptoms of shingles may feel like you're coming down with a cold or flu — fever, chills, headache, fatigue, nausea, upset stomach — accompanied by pain, burning, or tingling in a particular area of your skin. After a few days, a patch or band of a bumpy red rash may appear on one side of your body, usually around the waist, stomach, or chest. The rash turns into painful, fluid-filled blisters (per Cleveland Clinic). If you have shingles symptoms and develop a rash, the National Institute on Aging recommends seeing a doctor within three days of the rash appearing.

Shingles commonly present as a painful, blistery rash somewhere on the torso, but the virus can also appear in or around the eye. According to a study published in the BMJ, shingles in the eye, or ophthalmic herpes zoster, can cause scarring and vision loss, and accounts for up to 20% of all shingles cases. Symptoms of ophthalmic herpes zoster may include a rash and swelling around the eye that can start from the tip of your nose up to your forehead. Symptoms in the eye itself include pain, throbbing, redness, tearing, blurry vision, and sensitivity to light (per Healthline).

Is shingles contagious?

Shingles is not contagious, but chickenpox is. According to the CDC, while you can't get shingles from another person with the disease, you can get chickenpox. If a person who has never had chickenpox comes into contact with someone who has shingles, that person can develop chickenpox (with the possibility of developing shingles later).

Unlike other viruses that spread via droplets in the air from coughing or sneezing, the varicella-zoster virus is spread by coming into contact with the fluid from the shingles blisters. This can happen through skin-to-skin contact or by touching clothing, a towel, or a blanket with the blister fluid on it. You are considered contagious until the blisters have dried up and crusted over.

If you have shingles, keep the rash covered to avoid touching, scratching, and spreading it, and wash your hands frequently. Stay away from anyone who hasn't had chickenpox or received the chickenpox vaccine, pregnant or nursing women, premature or low-birth-weight infants, and anyone with a weakened immune system from cancer, HIV, chemotherapy, and radiation treatments.

There is no cure for shingles, but treatments are available that can help lessen the pain, duration, and severity of the illness. Fortunately, you can be proactive in preventing shingles by getting vaccinated.

How vaccines work in the body

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), your first line of defense to stop disease-causing pathogens like the shingles virus from entering your body is the physical barrier (e.g. skin, cilia). If the virus breaches these barriers, they cause an infection, attacking and multiplying. Once this happens, the second line of defense is your immune system, which can help attack and destroy the viral intruders.

In addition to the disease they carry, pathogens contain an antigen that helps the immune system produce the antibodies needed to fight that specific disease. Our bodies produce specific antibodies for each new pathogen we're exposed to. It can take a while for the immune system to make those antibodies, so until they are made, you are susceptible to that disease. However, once the antibodies become part of your immune system, they "remember" the antigen and work with the rest of the immune system to stop the pathogen in its tracks should it reappear. Each time that pathogen reappears, the antibody's memory helps produce a stronger and faster immune response.

Vaccines can play an essential part in this immune response. As WHO states: "Vaccines contain weakened or inactive parts of a particular organism (antigen) that triggers an immune response within the body." Even though the vaccine contains a part of the virus (or, in the case of newer vaccines, the blueprint for antigen creation), it won't cause the disease. Instead, it will prompt the immune system to produce antibodies.

The shingles vaccine

You might be thinking that since only one virus causes both chickenpox and shingles, the chickenpox vaccine could prevent you from getting shingles. However, that's not the case. As a matter of fact, it took about a decade after the chickenpox vaccine's debut before the first shingles vaccine was released to the public (per Healthline).

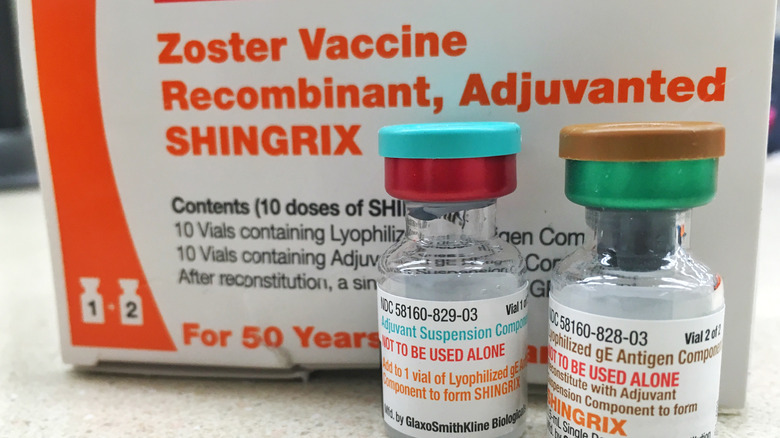

Shingrix was introduced in 2017 and is currently the only FDA-approved vaccine for shingles. Before Shingrix, Zostavax, a single-dose vaccine, came on the scene in 2006. Unfortunately, Zostavax proved to be less effective than Shingrix and was taken off the market in November 2020. If you received Zostavax, the CDC strongly suggests that you get the Shingrix vaccine as well.

Depending on your insurance plan, you may be able to get the shingles vaccine for little or no cost if you are on Medicare Part D or Medicaid, or if you have private health insurance (per CDC). If you don't have insurance coverage, you may be eligible for free vaccines through the GlaxoSmithKline patient assistance program for vaccines.

Who should get the shingles vaccine?

The CDC recommends that all healthy adults ages 50 and up get the shingles vaccine, regardless of whether or not they have had chickenpox. Your immune system declines with age, increasing your risk for shingles. Also, 99% of adults born before 1980 have had chickenpox. Even if you don't remember having chickenpox or the case was so mild it went undetected, the shingles virus is present in your body.

If you've ever had shingles, you should get vaccinated. Adults 19 years and up with a weakened immune system should also be vaccinated. If you received Zostavax, the previous shingles vaccine that was discontinued in November 2020, you should get the new Shingrix vaccine. Even if you received the chickenpox vaccine, the CDC still recommends that you get the shingles vaccine.

The CDC does not recommend the vaccine for pregnant or breastfeeding women. It should also not be taken if you're allergic to any of the ingredients in the vaccine, or have had a severe allergic reaction to the first dose of the vaccine. If you currently have shingles, you should wait until after the shingles rash is gone before getting vaccinated. If you have a moderate cold, the flu, or a fever, it's best to wait until you've recovered to be vaccinated.

If you are tested and have a negative result for the varicella-zoster virus, this means you never had chickenpox (per Healthline). Instead of the shingles vaccine, get the chickenpox vaccine.

What's in Shingrix and how effective is it?

Shingrix is a two-dose vaccine given in the upper arm, with the second dose being administered two to six months after the first (per Healthline). According to the CDC, the Shingrix vaccine is made with the lyophilized gE antigen and AS01B adjuvant suspension component. The vaccine does not have the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal. Thimerosal was previously linked with autism, but studies later found no association between vaccines containing thimerosal and autism.

Shingrix is a recombinant vaccine. As the Boston Museum of Science explains: "A recombinant vaccine uses the proteins of a virus to activate the immune system. These proteins are made in the laboratory by cells that use recombined pieces of the viral genetic code to turn out proteins." The Department of Health and Human Services says that recombinant vaccines are safe and effective for almost everyone and provide a robust immune response. Some other common recombinant vaccines include vaccines for hepatitis B, HPV (human papillomavirus), and whooping cough.

How effective is Shingrix? While no vaccine is 100% effective, according to the Cleveland Clinic, "The shingles vaccine is 97% effective in preventing shingles in people ages 50 to 69 years old. It's 91% effective in people ages 70 years and older." Additionally, it is said to be 91% effective in preventing painful postherpetic neuralgia in people ages 50 to 69 years old, and 89% effective in people ages 70 years and older.

What are the side effects of the Shingrix vaccine?

The Shingrix vaccine is safe for most people, and there is no age limit for receiving the vaccine (per CDC). Side effects are usually mild and short-lived, and appear within a few days of the first or second dose. The most common side effect is a sore arm including redness or welling around the injection site. Other possible side effects include fatigue, muscle pain, headache, fever, stomach pain, and nausea. The side effects usually last about two to three days and can be treated with over-the-counter pain medication like acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

Severe but less common side effects reported are severe allergic reactions, including hives, swelling of the face and throat, difficulty breathing, increased heart rate, weakness, and dizziness. If you have any of these symptoms, you should seek medical attention immediately. There have also been rare cases reported of developing Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a rare disorder where the body's immune system attacks the nerves, after receiving the vaccine. There is also a small increased risk of developing GBS after having shingles (per CDC).

Can you still get shingles (or get shingles again) if you've been vaccinated?

Unfortunately, you can still get shingles after being vaccinated. With that said, in the event you do get shingles, the symptoms are usually milder and last for a shorter time if you're vaccinated. Your risk of developing severe complications like postherpetic neuralgia is also lower (per the Cleveland Clinic).

More bad news: Although it's uncommon, it's possible to get shingles more than once (via WebMD). You're more likely to get shingles again if you're a woman, have a weakened immune system, were 50 years of age or older the first time you had shingles, or had severe pain lasting longer than 30 days during your first round of shingles. If you get shingles again, the rash will likely appear in a different area of the body. Again, getting the vaccine can help lessen the severity of the symptoms and duration of the episode.

Are there medications available to treat shingles?

According to the CDC, between 1% and 4% of shingles cases require hospitalization for complications, and there are less than 100 deaths per year due to shingles. Hospitalization and death usually occur in the elderly or people with compromised immune systems, and most cases of shingles can be treated at home.

There is no cure for shingles, but antiviral drugs such as acyclovir (Zovirax), valacyclovir (Valtrex), and famciclovir can help reduce the duration and severity of the episode, as well as the risk of developing severe complications (per CDC). These drugs work best when taken as soon as possible, so contact your doctor within three days of developing a rash to begin treatment.

You can take an over-the-counter pain medication like acetaminophen or ibuprofen to reduce the fever and manage the pain. For severe pain, your doctor may prescribe a stronger pain medication (per CDC), topical medications like capsaicin (per the Mayo Clinic), a numbing agent like lidocaine, corticosteroids, or local anesthetics injections. Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline have also been shown to help manage shingles pain.

Home remedies to help relieve shingles symptoms

To relieve itching, apply cool, moist compresses, take a cool bath or shower, or a lukewarm bath with 1 to 2 cups of colloidal oatmeal or cornstarch, according to Healthline. Apply calamine lotion to the rash after bathing to help stop the itching and dry out the blisters. If you don't have calamine lotion, you can make your own itch-relieving paste. Mix two parts cornstarch or baking soda and one part water. Apply the paste to your rash, let it dry for about 10 to 15 minutes, then rinse off. Repeat this several times a day as needed.

The National Institute on Aging recommends wearing loose-fitting clothes to stay comfortable and avoid placing pressure on the blisters. Shingles can be extremely painful, so keep yourself busy to distract you from the pain. Call a friend, do crossword puzzles, watch TV, or read a book. Keep your hands and mind busy by working on jigsaw puzzles or hobbies like crocheting or painting. As difficult as it may be, try to avoid getting stressed out, as it will only make the pain worse. Taking a leisurely walk or doing some gentle stretching can help reduce stress. Above all, don't try to push yourself. Get some rest and give your body the time it needs to recover.