The Unexpected Origins Of Human Teeth: From Skin Scales To Bone

You hardly give them any thought, yet throughout the day, your teeth play critical roles in your life. Enabling you to enunciate words properly, chew food for better digestion, and greet other human beings without having to utter a single sound, the teeth are unsung heroes that, more often than not, only receive admiration and care in front of the bathroom mirror, after meals, and before bedtime. (Here are some mistakes everyone makes when brushing their teeth.) Your teeth can also reveal some surprising things about your health, alerting you to a potential undiagnosed disease or that it's time to see a doctor.

But have you ever thought about how humans developed teeth in the first place? As explained in a 2009 article in the Journal of Anatomy, evidence suggests that humans and rodents share a common mammalian ancestor that possessed a set of teeth much like modern man's chompers. But where, exactly, did these tough yet tiny tools come from, and how did they end up in the mouth? As it turns out, this question has long been a point of contention among scientists, and the two predominant theories on the origin of teeth are, curiously enough, direct opposites.

Two tooth theories

Some experts say that scales on the skin slowly evolved into teeth over the course of prehistory (outside-in), while others believe that teeth first grew inside the body, with no connection to the external traits of our progenitors (inside-out).

A 2003 paper published in Evolution & Development sheds more light on the inside-out theory. Analysis of fossil evidence led experts to theorize that teeth may have first developed from one of the three embryonic layers (the endoderm), a phenomenon that happened independently from jaw evolution. Proponents of this theory have suggested that teeth originally grew in the pharynx in vertebrates that didn't have jaws, and that over time, they moved to the inside of the mouth.

On the opposite end of the debate is the outside-in camp, which also analyzed prehistoric data but came to a different conclusion. It's been said that the armor-like scales of fossil fish — yes, coverings that were very much outside the body — may have eventually "migrated into the mouth cavity," as mentioned in a 2009 study in the International Journal of Biological Sciences.

How ancient fish may help us understand the possible origins of teeth

Two of the most recent studies supporting the "outside-in" theory involve in-depth examinations of some rather bizarre-looking fish.

Authors of a 2015 study in Biology Letters examined fossils of Romundina, an extinct scaly fish that dates back to over 400 million years ago, and determined that it was the earliest-known manifestation of teeth in the fossil record. Using X-rays and computer modeling techniques, the researchers were able to form a theory as to how teeth developed in this armored Devonian-era swimmer, acknowledging the possibility that it developed teeth in order to become a more effective hunter, nabbing prey near the water's surface.

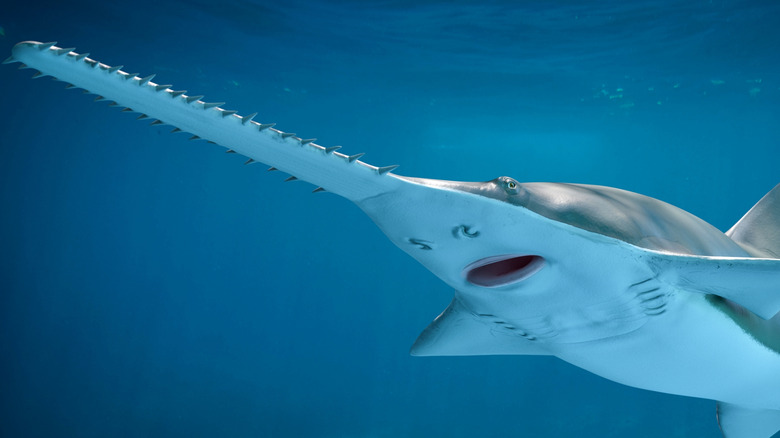

Meanwhile, in a 2022 study in the Journal of Anatomy, researchers focused on Ischyrhiza mira, a sawfish ancestor that lived during the same time as the world's last dinosaurs. It sported similar sawtooth-esque features as the ones on the elongated snouts of modern-day sawfish (aka rostral denticles), which are used not just for gathering food but also for warding off potential threats. While these sharp features aren't quite the same as actual teeth, they did possess characteristics that clued the scientists in on their surprising link.

How skin scales became bone: a possible explanation

The authors of the 2022 study didn't initially set out to investigate the origins of teeth, but what they found left them with no choice but to bite.

After looking at the rostral denticles of Ischyrhiza through an electron microscope, they realized that their internal crystalline structure more closely resembled the teeth of sharks. This was different from what the scientists expected to see, which was a closer resemblance to the dermal denticles (scales) that one would note after running their hand across the scaly, sandpaper-like body of a ray, shark, or sawfish.

From the way the rostral denticles of Ischyrhiza mira were constructed, they'd be strong enough to withstand physically stressful actions such as biting or chewing (aka the purpose that teeth would eventually serve). This added support to the theory that over time, these pseudo-proto-teeth likely made their way to the inner cavity of the mouth and, over years and years of evolution, formed an optimized system for breaking down food.

The tooth of the matter

Still, despite the amount of data studied in support of both theories of tooth evolution, we haven't reached a conclusive answer as to which of the two is more correct. With that said, the question of where teeth really came from is far from the only masticulation-related mystery that humanity has been pondering.

For instance, despite the fact that teeth are critical for our survival, they still, somehow, grow in some truly uncomfortable ways (e.g., crooked teeth, overbites or underbites, wisdom teeth that you need to get removed). One would think that, over time, evolution would have found a way to optimize the development of features that are so necessary for sustenance and communication.

There's also the fact that humans, like many other mammals, replace their primary teeth with a set of permanent teeth only once in their lifetimes since over 200 million years ago; meanwhile, reptiles, amphibians, and fish are polyphodonts, meaning they continually replace their teeth. That's a huge part of the reason why humans go to great lengths to maintain the strength and aesthetic quality of their teeth, which, despite technically not being bones, are the hardest parts of the body. (Here are some foods to eat — and to avoid — to whiten your teeth.)

Strangely enough, some vertebrates don't have teeth

It's hard to imagine how life would be without teeth, which is why it might surprise you to know that a fair number of vertebrates actually don't have them.

Some mammals (e.g., aardvarks, armadillos, sloths) have teeth sans enamel, a feature that allows them to keep growing and regrowing teeth. Pangolins are also toothless, relying on their sticky tongues to secure sustenance. On the reptilian side of things, turtles haven't had teeth for millions of years; instead, today's chelonians have strong beaks and jaws to make feeding easier.

And then, there are birds, the evolutionary heirs of ferocious meat-eating dinosaurs who have somehow ended up completely toothless. Instead, their beaks and digestive tracts work in tandem to make digestion possible. According to a 2014 study in Science, birds likely lost teeth at around the same time they developed their beaks, a process that started over a hundred million years ago.

Ultimately, while we still can't trace the origin of our teeth with 100% certainty, there's a strong case to be made that taking a closer look at the dental evolution (or lack thereof) of other animals may one day lead us to the truth.