An Experimental Treatment That Helped Cancer Patients Live 40% Longer Had One Noticeable Side Effect

Every year, about 1.7 million people in the United States are diagnosed with cancer, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Although there is no cure for cancer, the American Cancer Society says that more people are surviving their diagnoses thanks to early detection, fewer smokers, and improved treatments. Today, cancer can be treated with surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or hormone therapy, depending on the type and stage of the disease.

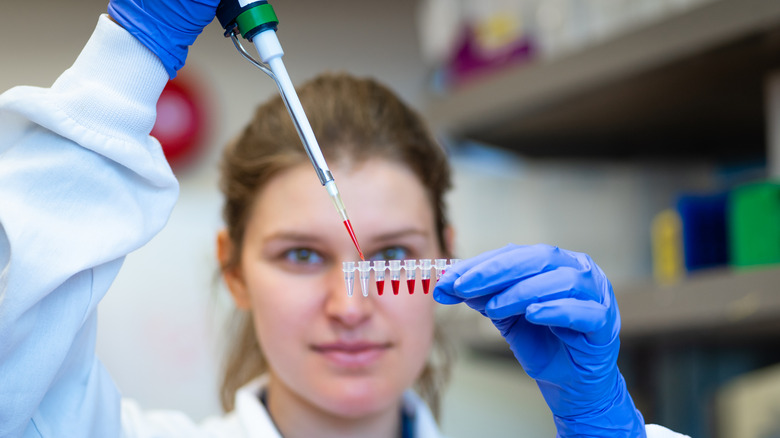

A new immunotherapy for treating stomach cancer is currently in phase 2 clinical trials, which further test the drug's effectiveness and safety. The treatment, called satricabtagene autoleucel (or satri-cel), is a type of CAR T-cell therapy. It works by training a patient's immune cells to target specific proteins that help cancer cells grow. A 2025 study published in The Lancet found that patients who received this immunotherapy lived, on average, 40% longer than those treated with standard cancer drugs.

As with any treatment or drug, there were side effects to the satri-cel treatment. Most people who received the immunotherapy experienced drops in their white blood cell and immune cell counts. All but four patients also developed cytokine release syndrome, a reaction that can occur in people undergoing immunotherapy.

What is cytokine release syndrome?

If you have an infection, a healthy immune system releases cytokines — proteins that influence the activity of blood and immune cells. During immunotherapy, however, the immune system can sometimes overreact and release too many cytokines. This condition, known as cytokine release syndrome (or a cytokine storm), can cause a range of inflammation-related symptoms, such as fever, muscle aches, and nausea. It may also affect the heart by causing low blood pressure or the brain by triggering seizures. Other symptoms may include cough, shortness of breath, and impaired liver or kidney function.

Patients receiving immunotherapy are typically monitored for cytokine release syndrome during the first few weeks after treatment. Mild cases can often be managed with corticosteroids or other drugs that target cytokines. More severe cases may require supplemental oxygen, IV fluids, dialysis, or blood transfusions. Recovery can take up to two weeks, depending on how serious the condition is.

Cytokine release syndrome can occur in up to 93% of patients who undergo CAR T-cell therapy, according to a 2021 study in Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. While the current study confirmed this relatively common side effect with satri-cel, the immunotherapy still offered hope to patients whose gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer didn't respond to at least two previous treatments. In fact, among patients who initially received standard drug therapy and later switched to satri-cel, 20% saw their tumors shrink.

Why CAR T-cell therapy may be necessary for cancer treatment

This experimental satri-cel immunotherapy treats stomach cancer and gastroesophageal junction cancer, which affects the junction of the stomach and esophagus. These types of cancer are the fifth most common cancers worldwide. The outlook is relatively poor if the cancer has advanced. What makes treating these cancers tricky is that sometimes patients develop resistance to the available treatments, especially if they've received several treatments. Without alternative treatments, they won't live as long.

Right now, the drug zolbetuximab targets the specific protein found in gastrointestinal cancers. It is used with chemotherapy in patients whose cancer is too advanced to be removed without surgery. Other treatments, such as monoclonal antibodies, show potential in treating these cancers, but they also involve chemotherapy, which can have significant side effects with multiple treatments.

According to the American Cancer Society, CAR T-cell therapies take immune cells (called T cells) from the patient and modify them so they target a specific cancer. Different cancers have specific antigens, so a CAR T-cell therapy to treat leukemia is different from one that targets stomach cancer. The T cells are then grown in the lab until enough cells are available for the treatment. The patient is then given an infusion of these T cells to fight the cancer. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several CAR T-cell therapies to treat types of lymphomas and leukemias.